Description

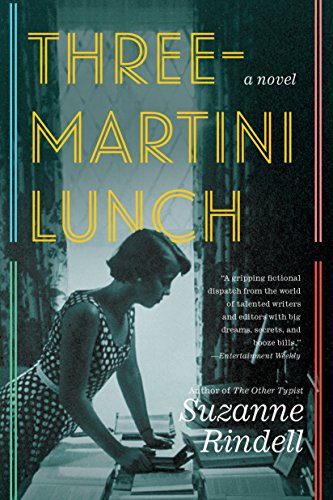

Praise for Three-Martini Lunch “Think of it as the publishing industry’s take on Mad Men : a gripping fictional dispatch from the world of talented writers and editors with big dreams, secrets, and booze bills.”— Entertainment Weekly “Packed with narrative surprises... Rindell keeps the suspense strong as we wonder if Eden and Cliff and Miles are fated for success or doomed to failure.”— CT Post “A rollicking period piece that builds to a magnificent crescendo. With an excellent ear for the patter and cadence of the time, Rindell expertly brings a bygone era to life, though the struggles of her trio feel anything but dated. While blackmail and backstabbing keep things suitably scandalous, Rindell also explores deeper issues of race, sexuality, class and gender in ways that feel vital and timely. The end result is a moving novel that proves provocative in more ways than one.”— BookPage “Sprawling across more than 500 pages, the new novel Three-Martini Lunch captures the excesses as well as the inhibitions of New York City in 1958, from the eponymous meals of the big Manhattan publishing houses, to wild drinking-and-drug bouts in Greenwich Village, to the lingering paranoia of McCarthyism, to the casual racism, sexism, homophobia and anti-Semitism among the professional class. ”—New York Journal of Books “Compulsively readable melodrama about life in the Manhattan publishing world of the 1950s… [Rindell] does it with such high style and draped in such alluring, gin-soaked detail that we overcome our critical selves and root like hell for Eden to become an editor, for Miles to accept his love for Joey, and for Cliff to quit being a jerk.” — Booklist “[ Three-Martini Lunch ] offers a captivating look into the vibrancy of mid-20th-century New York City through the eyes of three flawed and therefore, fascinating young characters.”— Library Journal “With its vivid historical setting and the narrators' distinct voices, this ambitious novel is both an homage to the beatnik generation and its literature, as well as an evocative story of the price one pays for going after one's dreams.” — Publishers Weekly “Suzanne Rindell’s latest novel is a riveting account of three young adults struggling to define themselves against issues of family, race, and sexual identity in the intolerant world of the '50s. Three-Martini Lunch is a gripping study of the ways in which people betray others and themselves in an effort to carve out places for themselves in a competitive and unforgiving world.”—Sara Gruen, New York Times -bestselling author of Water for Elephants and At the Water’s Edge “Set in New York City's Beat Generation, a skillfully crafted story of three young professionals trying to make it big in publishing: This is Three-Martini Lunch .xa0 Their choices and sacrifices ripple out from the pages and shake our hearts. A gripping read.”—Sarah McCoy, New York Times -bestselling author of The Mapmaker's Children “ Three-Martini Lunch does for publishing what Mad Men did for advertising. It takes you back in time and then proceeds to etch in a whole world, stroke by stroke. This fast-moving novel is rich with incident and wonderfully conflicted characters.”—James Magnuson, author of Famous Writers I Have Known Suzanne Rindell is the author of two novels, The Other Typist and Three-Martini Lunch . xa0Rindell spent most of her life in Northern California (Sacramento and San Francisco), but currently lives in New York City, where she is at work on a third novel. From Publishers Weekly In Rindell's second novel (after The Other Typist), the lives of three young people intersect over literature and ambition during the height of the beatnik era in Greenwich Village. Cliff Nelson, the son of a powerful New York editor, wants to be a famous writer but spends less time writing than emulating Hemingway's drinking. Eden Katz, a transplant from Indiana who remakes herself in the style of Holly Golightly, has her sights set on being an editor at a big New York publishing house. After Eden is hired as a secretary to Cliff's father, she and Cliff secretly elope. Meanwhile, the literary ambitions of Miles Tillman, a quiet, gay, black Columbia graduate from Harlem, are repeatedly tested by personal and societal road blocks. After Miles is attacked at a party hosted by Cliff and Eden, he heads to San Francisco, where he finds his father's WWII journal. The journal—along with his relationship with the man who helped him find it—provides Miles with plenty of fodder for writing, but he becomes inexorably tangled in Cliff and Eden's struggles for literary success. With its vivid historical setting and the narrators' distinct voices, this ambitious novel is both an homage to the beatnik generation and its literature, as well as an evocative story of the price one pays for going after one's dreams. Agent: Emily Forland, Brandt & Hochman Literary Agents. (Apr.) --This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. ***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected proof***Copyrightxa0© 2016 Suzanne Rindell Cliff 1 Greenwich Village in ‘58 was a madman’s paradise.xa0 In those days a bunch of us went aroundtogether drinking too much coffee and smoking too much cannabis and talking allthe time about poetry and Nietzsche and bebop.xa0I had been running around with the same guys I knew from Columbia – giveor take a colored jazz musician here or a benny addict there – and together wewould get good and stoned and ride the subway down to Washington Square.xa0 I guess you could say I liked my Columbiabuddies all right.xa0 They were swellenough guys but when you really got down to it they were a pack of poserwannabe-poets in tweed and I knew it was only a matter of time before I outgrewthem.xa0 Their fathers were bankers andlawyers and once their fascination with poetic manifestos wore off they wouldsettle down and become bankers and lawyers, too, and marry a nicedebutante.xa0 I was different from theseguys because even before I went to college I knew I was meant to be an artist,even if I didn’t know just yet exactly what form I wanted my creativity totake.xa0 As far as I was concerned academiawas for the birds anyhow, and the more I spent time below 14thStreet, the more I realized that the Village was my true education. When I finally threw in the towel and dropped my last classat Columbia, My Old Man came poking around my apartment in MorningsideHeights.xa0 He ahemmed quietly to himself and fingered the waxy leaves of theplants in the window and finally sat with his rump covering a water-stain on ahand-me-down Louis XVI sofa my great-aunt had deemed too ugly to keep in herown apartment.xa0 Together we drank acouple of fingers of bourbon neat, and then he shook my hand in a dignified wayand informed me the best lesson he could teach me at this point in my life was self-reliance .xa0 His plan mainly involved cutting me off fromthe family fortune and making long speeches on the superior quality of earned pleasures . Once My Old Man broke the news about how I was going tohave to pave my own road it was all over pretty quickly after that.xa0 I threw a couple of loud parties and didn’tpay my rent and then the landlord had me out lickety-split and I had to golooking for a new place. Which is how, as I entered into mystudy of the relative value of earned pleasures, I found myself renting aone-room studio in the Village with no hot water and a toilet down thehall.xa0 The lid was missing on the tank ofthat toilet and I remember the worst thing I ever did to my fellow hall-mateswas to get sick after coming home drunk one night and mistake the open tank forthe open bowl.xa0 But even without mywhiskey-induced embellishments the building was a dump.xa0 It was a pretty crummy apartment and when itrained the paint on the walls bubbled something awful, but I liked being nearthe basement cafés where people were passionate about trying out new thingswith the spoken word, which was still pretty exciting to me at the time.xa0 In those days you could walk the streets allaround Washington Square and plunge down a narrow stairway here and there tofind a room painted all black with red light bulbs screwed into the fixturesand there’d be someone standing in front of a crowd telling America to go tohell or maybe acting out the birth of a sacred cow in India.xa0 It was all kind of bananas and you were neversure what you were going to see, but after a while you started to come acrossthe same people mostly. I had seen Miles, Swish, Bobby, and Pal around theVillage, of course, and they had seen me, too.xa0We were friendly enough with one another, all of us being artytypes.xa0 I knew their faces and I knewtheir names but the night I really entered the picture I was in such a sorrystate it was a real act of mercy on their part.xa0I was slated to read my poems for the first time ever at a place calledThe Sweet Spot. Earlier that afternoon I had been looking over my pages when itsuddenly struck me they were no good.xa0The discovery had me seized me up with fear until my whole body wasparalyzed and I sensed I was rank with the stench of my impending failure.xa0 The poems were bad and that was the truth ofit.xa0 My solution was whiskey, and by sixo’clock I had managed to put down half a bottle before the poems finallystarted to look better than they had at three p.m.xa0 In my foolish state I decided finishing theother half of the bottle would be the key to gaining at least a few moreincrements of poetic improvement.xa0 By thetime I took the stage I could barely hold myself upright.xa0 Somehow I managed to get off two poems… moreor less… before I heard the wooden stool next to me clatter to the ground as itfell over and I felt the cold sticky black-painted floor rise up like aswelling wave to my hip and shoulder and, seconds later, my face. When I came to I was lying on a couch in Swish’s apartmentwith the whole gang sitting around the kitchen table talking in loud voicesabout Charlie Parker while a seminal record of his spun on a turntable near myhead.xa0 After a few minutes Pal came overand handed me a cool washcloth for my bruised face.xa0 Then Bobby whistled and commented that I had“ some kind of madman style” in anadmiring tone of voice that made me think perhaps the two poems I couldremember getting off hadn’t been so bad after all and maybe it was even truethat in getting wasted I had actually made the truest choice an artist couldmake, like Van Gogh and his absinthe.xa0 Icould see they were all deciding whether I was a hack or a genius and the factthey might be open to the second possibility being true fortified me and filledme with a kind of dopey pride.xa0 ThenSwish boiled some coffee on the stove and brought it over to me.xa0 He told me his religion was coffee and hecouldn’t abide his guests adding milk or sugar and so I shouldn’t ever expecthim to offer any of that stuff.xa0 Thecoffee was so thick you could have set a spoon in the center of the mug and itwould’ve stood up straight and never touched the sides.xa0 Later when I learned more about Swish he toldme that was how you made it when you were on the road and once you’d had yourcoffee like that everything else tasted like water.xa0 I guess some of Swish’s romantic passionabout cowboy coffee wore off on me, because after that night I sneered atanything someone brought me that happened to have a creamy shade or sweetenedtaste. Swish’s given name was Stewart and he was nicknamed Swishbecause he was always in a hurry.xa0 He wasone of those wiry, nervous guys with energy to spare.xa0xa0 After I’d taken a few sips of Swish’s coffeeand managed to work my forehead over some more with the washcloth I was feelingwell enough to join them at the kitchen table and dive into the talk aboutDizzy Gilespie and Charlie Parker, and all of a sudden it was like I had alwayshad a seat at that table and had just never known it.xa0 The frenzied tempo of their chatter wascontagious.xa0 They conversed likemusicians improvising jazz and I hoped some of this would find its way into mywriting.xa0 Between the five of us wefinished off a pot of coffee and two packs of cigarettes and fourteen bottlesof beer and shared the dim awareness that a small but sturdy union had beenformed. Swish regaled us with his adventures riding the railsacross America like a hobo and about the year he’d spent in the MerchantMarines.xa0 Even though he’d never finishedhigh school he had still managed to feed his mind all sorts of good solid stuffand in talking to Swish I realized all those guys at Columbia who thought theyhad the edge over you because they went to Exeter or Andover were all prettymuch full of horseshit because here was Swish and he was better-read thananybody and his education had been entirely loaned out to him from the publiclibrary for no money at all.xa0 There was amoment when I worried that maybe I’d offended Swish because I said something toset him off and he went on to give a big argumentative lecture all about JohnLocke and Mikhail Bakunin and about Thoreau.xa0But my worries about having offended him were unfounded because I laterrealized Swish was one of those guys with a naturally combative disposition. After he’d finished harping on old Mikhail’s theoriesabout anarchy I asked Swish what he did for a living now his hobo days wereover. “Bicycle messenger,” he replied.xa0 “Miles here is, too.” I regarded Miles, who seemed like an odd fit for thisgroup.xa0 He was a slender,athletic-looking Negro with sharp cheekbones that would’ve made him appearhaughty if they had not been offset by his brooding eyes.xa0 He wore the kind of horn-rimmed glasses thatwere popular all over the Village just then.xa0He nodded but didn’t comment further and I gathered that being a bicyclemessenger wasn’t his primary passion and figured him for a jazz musician.xa0 He had the name and the look for it, afterall. Anyway, the topic of conversation turned to me and what myambitions were and sitting there at the table I already felt so comfortable andeverything seemed so familiar I found myself confessing to the fact I’drecently come to the conclusion that I’d decided to become a writer.xa0 Only problem was, ever since I’d arrived atthis decision, I’d been having a spell of writer’s block. “I’ll tell you what you do,” Swish said, his wiry bodytensing up with conviction. “You hop on the next boxcar and ride until you’refull up with so many ideas you feel your fingers twitching in your sleep.” “Well, I for one think a good old-fashioned roll in thehay would do the trick,” Bobby chimed in.xa0“It’s important to keep the juices flowing.” “Says the fella who’s so busy balling two girls at once hecan’t make it to any of his auditions,” said Swish.xa0 I asked them what they meant.xa0 It turned out Bobby wanted to be an actor buthis great obstacle in achieving this ambition was his overwhelming beauty.xa0 Under ordinary circumstances this wouldn’t bea problem for an actor but in Bobby’s case it kept him far too busy to getonstage much.xa0 Wherever he wentloud-shrieking girls and soft-spoken men alike tried their best to bed him andbecause Bobby liked to make everyone happy he went along with all of it and wasloath to turn anyone down.xa0 He waspresently keeping two girls in particular happy.xa0 One girl lived with a roommate over on MortonStreet and the other lived in the Albert Hotel on East 11th and this left Bobbyconstantly hustling from one side of the Village to the other. Bobby’s recommendation that I ought to ball a girl (or twoor three) to get over my writer’s block appeared to disturb Pal’s sense ofchivalry and make him shy: He shifted in his chair and set about studying thelabel on his beer.xa0 He was by far thequietest and most difficult guy to read of the pack.xa0 Later I found out Pal’s real name was Eugeneand he was named after the town in Oregon where he was born and as far as firstimpressions go he often struck people as something of a gentle giant.xa0 He was a couple of inches over six feet andhad the sleepy blue eyes of a child just woken up from a nap and when he readpoetry or even when he just spoke his voice was always full of a kind ofreverence that made you think he was paying closer attention to the world thanyou were. “How ‘bout it, Miles?” Swish said, continuing theconversation.xa0 “What do you think helpswith writer’s block?” I didn’t know why Swish had directed the question toMiles.xa0 It unnerved me that after Imentioned dropping out of Columbia, Bobby had let it slip that Miles was due tograduate from that very institution come June.xa0The lenses of Miles’s glasses flashed white at us as he looked up insurprise. “Well,” he said, considering carefully, “I suppose readingalways helps.xa0 They say in order to writeanything good, you ought to read much more than you write.” “Oh, I don’t know about all that,” I said.xa0 I was suddenly in an ornery, contrarymood.xa0 The way he had spoken withauthority on the subject antagonized me somehow.xa0 “The most important thing a writer’s gotta dois stay true to his own ideas and write.xa0I don’t read other people’s books when I try to write, I just read myown stuff over and over and I think that’s the way the real heavyweight authorsdo it.” Miles didn’t reply to this except to tighten his mouth andnod.xa0 It was a polite nod and I sensedthere was a difference of opinion behind it and I was suddenly annoyed. “Anyway, fellas, I think I’ve given you the wrong ideaabout me because I’m not really all that stuck,” I said, deciding it was timefor a change of topic.xa0 “I’ve writtenpiles and piles of stuff and I’m always getting new ideas.” This was mostly true, and the more I thought about it nowthe more I began to think perhaps it wasn’t writer’s block at all but more acase of my energies needing to build up in order to reach a kind of criticalmass.xa0 Back then everyone in theneighborhood was talking about a certain famous hipster who had written anentire novel in three weeks on nothing but coffee and bennies and about how hehad let it build up until it had just come pouring out of him and about how theresult had been published by an actual publisher and I thought maybe that washow it might work for me, too.xa0 If I justsoaked up the nervous energy of my generation and let it accumulate inside meuntil it spilled over the top I was sure eventually a great flood wouldcome.xa0 Swish and Bobby and Pal all seemedlike part of this process and I was very glad they had inducted me into thegroup.xa0 Even Miles was all right in theway that a rival can push you to do better work.xa0 Perhaps it was the mixture of the whiskey andcoffee and beer and bennies but I suddenly had that high feeling you get whenyou sense you are in the middle of some kind of important nerve center.xa0 I closed my eyes and felt the pulse of theVillage thundering through my veins and all at once I was very confident aboutall I was destined to accomplish. 2 Looking back on it now, I see that New York in the 50’smade for a unique scene.xa0 If you lived inManhattan during that time you experienced the uniqueness in the colors andflavors of the city that were more defined and more distinct from one anotherthan they were in other cities or other times.xa0If you ask me, I think it was the war that had made things thisway.xa0 All the energy of the war effortwas now poured into the manufacture of neon signs, shiny chrome bumpers, brightplastic things and that meant all of a sudden there was a violent shade ofFormica to match every desire.xa0 All of itwas for sale and people had lots of dough to spend and to top it off the atombomb was constantly hovering in the back of all our minds, its bright whiteflash and the shadow of its mushroom cloud casting a kind of imaginary yeturgent light over everything that surrounded us. Shortly after the fellas revived me at Swish’s apartment,I fell in regularly with the gang and soon enough I found out Miles was awriter, too.xa0 I should’ve known all alongbecause everyone who was young and hip and living in New York at that time allwanted to do the same thing and that was to try and become a writer.xa0 Years later they would want to become folkmusicians or else potters who threw odd-shaped clay vases but in ’58 everyonestill wanted to be a writer and in particular they wanted to write somethingtruer and purer than everything that had come before. There were a lot of different opinions as to what it tookto make yourself a good writer.xa0 Thepeople in the city were always looking to get out and go West and the peopleout West were always looking to get into the city.xa0 Everybody felt like they were on the outsidelooking in all the time when really it was just that the hipster scene tendedto turn everything inside out and the whole idea was that we were all outsiderstogether. I had always scribbled here and there but I didn’t try towrite in earnest until I left Columbia and got cut off and moved to the Villageand this was maybe a little ironic because My Old Man was an editor at a bigpublishing house.xa0 He had wanted to be awriter himself but had gone a different way with that and had become an editorinstead, although he never said it that way to people who came for dinner.xa0 When people came over for dinner he mostlyjust told jokes about writers.xa0 It turnsout there are lots of jokes you can tell about writers. I had a lot of funny feelings about My Old Man.xa0 On the one hand, there was some pretty lousybusiness he’d gotten into in Brooklyn that he didn’t think I knew about.xa0 But on the other hand he was one of thoselarger-than-life types you can’t help but look up to in spite of yourself.xa0 He had a magnetic personality.xa0 Back in those days My Old Man was king ofwhat they called the three-martini lunch.xa0xa0This meant that in dimly lit steakhouses all over Manhattan my fathermade bold, impetuous deals over gin and oysters.xa0 That was how it was done.xa0 Publishing was a place for men with ferocityand an appetite for life.xa0 Sure, the shy,tweedy types survived in the business all right but it was the garrulous bon vivants who really thrived and lefttheir mark on the world.xa0 Lunches werelong, expense accounts were generous, and the martinis often fueled tremendousquantities of flattery and praise.xa0 Ofcourse all that booze fueled injuries too and the workday wasn’t really overuntil someone had been insulted by Norman Mailer or pulled out the old boxinggloves in one way or another. I was passionate about being a writer and My Old Man waspassionate about being an editor and you would think between the two of us this would make for a bang-upcombination, but my big problem was that My Old Man and I had our issues and Ihadn’t exactly told him about my latest ambitions.xa0 He’d always expressed disappointment over mylackluster performance in school and now that I’d dropped out was spending allmy time in the Village he thought I was a jazz-crazed drunkard.xa0 His idea of good jazz was Glenn Miller and itwas his personal belief that if you listened to any other kind you were adope-fiend of some sort. But whether or not My Old Man ever helped me out, I wasdetermined to make it as a writer.xa0 Infact, sometimes it was more satisfying to think about becoming a writer withoutMy Old Man even knowing.xa0 I’d written acouple of short stories that, in my eyes, were very good and it was onlylogical that in time I would write a novel and that would be good, too.xa0 I thought a lot about what it would be likeonce I made it, the swell reviews I would get in the Times and the Herald Tribune aboutmy novel, the awards I’d probably win, and how all the newspaper men would wantto interview me over martinis at the 21 Club.xa0But the problem with this is sometimes I got so caught up in my headwriting imaginary drafts of the good reviews I was bound to receive it made itdifficult to write the actual novel. On days when I was having trouble punching the typewriterI began to find little errands to run in the evenings that usually involved goingdown to the cafés in order to tell Swish and Bobby and Pal something importantI had discovered that day about writing and being and existence.xa0 After I had delivered this message of courseit was necessary to stay and enjoy a beer together and toast the fact we hadbeen born to be philosophers and therefore understood what it was to really be .xa0Sometimes Miles was there and sometimes he was not and I didn’t alwaysnotice the difference because he was so reserved and only hung around our groupin a peripheral way. But Miles was there one afternoon when I went to a café to write.xa0 I had decided my crummy studio apartment waspartly to blame for my writer’s block and that I ought to try writing in acafé.xa0 After all, Hemingway had writtenin cafés when he was just starting out in Paris and if that method had workedfor Hemingway then I supposed it was good enough for me.xa0 The café I happened to choose was verycrowded that day and the tables were all taken when I got there but I spiedMiles at a cozy little table in the far corner of the room and just as Ispotted him he looked up and saw me too. “Miserable day outside,” I said, referring to therain. “Yes.” Miles and I had never spent time together on our own andnaturally now that were alone there was an awkwardness between us and it dawnedon both of us how little we truly knew each other.xa0 I squinted at the items on the table in anattempt to surmise what he had been up to before I had come in. “Are you writing something too?” I asked, seeing thenotebook and the telltale ink stain on his thumb and forefinger. “I’m only fooling around,” Miles answered, but I couldtell this was a lie because peeking out of his notebook were a few typewrittenpages, which meant whatever Miles was working on he cared about enough to takethe trouble to type it up. “I see you own a typewriter,” I said, pointing to thepages. “The library does,” he said, looking embarrassed.xa0 I couldn’t tell whether the embarrassment wasdue to the fact he was too poor to own a typewriter or because it was obvioushe took his writing more seriously than he’d wanted to let on. “They charge you for that?” I asked, trying to makeconversation. He nodded.xa0 “Tencents a half hour.xa0 It’s not toobad.xa0 I’ve taught myself to type at a fairlygood speed now.” “That’s swell,” I said.xa0“Say, do you mind if I settle in here and do a little scribbling of myown?” I asked, finally getting to my point. “Of course not,” Miles said, pushing a coffee mug and somepapers out of the way on the table.xa0 Hehad a very polite, formal way about him and it was difficult to tell whether hetruly minded.xa0 But whether he did or notdidn’t matter because after all he’d said yes and I needed to write and therereally weren’t any other tables and I wasn’t going to go look for another cafébecause by then it was really coming down cats and dogs outside.xa0 I pulled out my composition book and fountainpen and set to work staring at the thin blue lines that ran across the whitepaper.xa0 About ten or so minutes passedand I had made a very good study of the blank page.xa0 Then my nose started to itch and my kneebegan to bounce under the table.xa0 Ilooked up at Miles and watched him scrawling frantically in his notebook.xa0 I was curious what it was that had gotten himworked up in a torrent like that.xa0 He wasso absorbed in his writing he didn’t notice me staring at him.xa0 Finally, I asked him what he was working on.xa0 The first time I asked he did not hear me soI cleared my throat and asked again, more loudly.xa0 He jumped as if I’d woken him out of a tranceand blinked at me. “It’s a short story, I suppose…” he said.xa0 This was news to me because, like I said,nobody had bothered to tell me Miles wrote anything at all, let alonefiction.xa0 Between his attending Columbiaand writing, I was beginning to feel a little unsettled by all the things wehad in common.xa0 Something about Miles wasmaking me itchy around the collar. “I don’t know if it’s any good,” he said. “Say, why don’t you let me have a look at it?” I replied,catching him off guard and reaching for the notebook before he could put up afight.xa0 “I know good fiction.xa0 My Old Man is an editor at Bonwright.”xa0 His eyes widened at this and I knew it hadtemporarily shut him up.xa0 I flipped thenotebook open and moved my eyes over the tidy cursive on the page. It wasn’t terrible.xa0Miles was a decent enough writer, all right – save for the fact that hewrote in a careful, old-fashioned voice, and that was probably on account ofhim being an educated Negro.xa0 All theeducated Negroes I’d ever known were always a little stiff and took theireducations a little too seriously in my opinion.xa0 But all and all, I could see he had a waywith words and it wasn’t half-bad. xa0I hadto admit I liked the story okay.xa0 It wasabout two boys on the warfront who discover they’re half-brothers but they’vealways been competitors and don’t like each other.xa0 When they get into a real bad scrape one hasthe option to let the other die and be off the hook for the death, but hehesitates. “How are you going to end it?” I said, coming to the placewhere the cursive trailed off.xa0 Milesshrugged. “Maybe just like that,” he said.xa0 “It was the hesitation that interestedme.” I shook my head.xa0“He should hesitate all right,” I said.xa0“And decide against his better sense to save his brother.xa0 But then when he does, the other fellowshoots him with the dead German’s gun, like the sucker he is.”xa0 Miles looked at me with raised eyebrows.xa0 I could see my suggestion was unexpected. “I suppose that would… make quite a statement.” “Exactly,” I said, feeling magnanimous for loaning out mysuperior creativity, “It’s not worth writing if it doesn’t make astatement.”xa0 Miles looked at me and Icould already see he wasn’t going to write it the way I suggested, which was amistake.xa0 It was a good twist and I hadmade a nice gift out of it for him and it was awfully annoying that he wasn’tgoing to take the wonderful gift I had just bestowed upon him. “Well, anyway,” I said, “suit yourself with theending.” I handed the journal back to him and attempted to get backto work.xa0 Miles sat there a momentlooking at me with a wary expression on his face.xa0 Then he turned back to his own work.xa0 We were silent together and all at once thewords started coming and I found I could write and for several minutes the onlysound you could hear at our table came from the scratching of our duelingfountain pens. But it was no good.xa0I had helped Miles along with his plot and now I couldn’t get it out ofmy head.xa0 I was off and running andwriting something but soon enough I realized I was just writing his story allover again, but better.xa0 The thing thatreally got to me as I wrote was that it really ought to have been my story in the first place.xa0 You shouldalways write what you know and I was something of an authority on unwantedrelatives, but of course Miles couldn’t know that.xa0 Now that he had started writing that story Icouldn’t go and write anything similar, even if he was going to botch the ending. “How’d you come up with the idea for that story anyway?” Iasked, feeling irritated that I hadn’t thought of it first.xa0 Miles looked up. “I was trying to remember some of my father’s storiesabout the Battle of the Marne; that’s why I picked the setting.xa0 And the idea of brothers and all the rest ofit…” he shrugged, “…just came out of my imagination.xa0 Like I said, I’m not sure it’s any good.xa0 I usually can’t tell about my own work untilseveral drafts and a few months later.” “Well, it has potential.xa0I wouldn’t take it too hard,” I said. “You strike me as a guy who workspretty hard at it, and that’s what counts, right?” Miles looked at me, not saying anything. “Say, I’m thirsty,” I said.xa0 “Why don’t we order up something strongerthan coffee?” After a brief bout of resistance he could see I wasn’tgoing to take no for an answer.xa0 We spentthe afternoon drinking and talking about the Pulitzer and the Nobel and thedifferences between French writers and Russian writers and to tell the truth Ihad a decent enough time talking to Miles.xa0I decided it would be fine if we ran into each other on our own again,so long as I didn’t have to sit across from him as he scribbled away in hisnotebook, writing the kind of stories I should’ve been writing but with all the wrong endings. --This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition. Read more

Features & Highlights

- From the author of the “thrilling” (

- The Christian Science Monitor

- ) novel

- The Other Typist

- comes

- an evocative, multilayered story of ambition, success, and secrecy in 1950s New York.

- In 1958, Greenwich Village buzzes with beatniks, jazz clubs, and new ideas—the ideal spot for three ambitious young people to meet. Cliff Nelson, the son of a successful book editor, is convinced he’s the next Kerouac, if only his father would notice. Eden Katz dreams of being an editor but is shocked when she encounters roadblocks to that ambition. And Miles Tillman, a talented black writer from Harlem, seeks to learn the truth about his father’s past, finding love in the process. Though different from one another, all three share a common goal: to succeed in the competitive and uncompromising world of book publishing. As they reach for what they want, they come to understand what they must sacrifice, conceal, and betray to achieve their goals, learning they must live with the consequences of their choices. In

- Three-Martini Lunch

- ,

- Suzanne Rindell has written both a page-turning morality tale and a captivating look at a stylish, demanding era—and a world steeped in tradition that’s poised for great upheaval.

- From the Hardcover edition.