Description

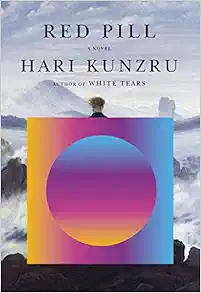

ONE OF THE LOS ANGELES TIMES' "20 READS BOOK PEOPLE ACTUALLY WANT THIS YEAR" “Haunting and timely . . . Kunzru is not the first to write about the free-floating dread and creeping paranoia brought on by the accelerated technologies and fluid social structures of modern life, but his innovation lies in having grafted a taut psychological thriller onto an old-fashioned systems novel of the sort Don DeLillo or Thomas Pynchon used to write. The effect is dizzying, and also delightful, as he riffs on everything from the early-nineteenth-century German writer Heinrich von Kleist to surveillance culture to the Counter-Enlightenment to the history of schnitzel, while somehow still clocking in at under three hundred pages.” —Jenny Offill, The New York Review of Books “An absorbing parable of contemporary paranoiaxa0. . .xa0Mr. Kunzru has always paired his sharp, elegant prose with visions of pandemoniumxa0. . . Current events, he suggests, illustrate the madness of the world more effectively than any literary device.” —Sam Sacks, The Wall Street Journal “If there is a lasting value to Red Pill , it is in its clever and thoughtful critique of the urge of many creative and purportedly progressive people to make themselves heroes—or at the very least historical subjects—at a moment in which they clearly have so little agency or role to play . . . Red Pill is perhaps Kunzru’s most overtly political novel. It not only engages the world of electoral politics but also offers an unsparing study of the flaccid state of 21st century liberalism and the intellectuals and creative types who hold on to its false promise of order and reason.” —Kevin Lozano, The Nation “Just finished reading Red Pill by Hari Kunzru. Astonishing, absorbing, terrifying. Immensely good." —Philip Pullman, author of the His Dark Materials trilogy “Dream-like, all-consuming . . . You want to read Hari Kunzru’s Red Pill to understand the madness of the past few years." —Nicholas Cannariato, NPR “Kunzru finds the humor and humanity in it all, but even as the story spirals into well-earned hysteria, he never downplays the severity of the mental derangement unfolding on both sides of the aisle in a post-truth era, nor the ways each can intersect in the realm of conspiracy.” —Randall Colburn, The A.V. Club “Hari Kunzru’s new book Red Pill is the Gen X Midlife-Crisis Novel in its purest formxa0. . . A funny and suspenseful novel, dense with ideas, deliciously plotted, and generous with its satirical acid.” —Christian Lorentzen, Bookforum “Deeply intelligent and artfully constructed . . . Kunzru devotes a lengthy — and riveting — section of the book to Monika’s story, vividly evoking the scruffy flats and sordid betrayals of East Berlin in the mid-1980s . . . For some writers, the gently comic potential of [ Red Pill ’s] set-up would be enough. But Kunzru is too ambitious to be satisfied by academic farce.” —Jonathan Derbyshire, Financial Times “Razor-sharp . . . as an allegory about how well-meaning liberals have been blindsided by pseudo-intellectual bigots with substantial platforms, it’s bleak but compelling . . . ‘Kafkaesque’ is an overused term, but it’s an apt one for this dark tale of fear and injustice.” — Kirkus (starred) “Dazzling . . . Kunzru has created a complex, challenging, and bold story about a world gone amok. . ." — Booklist (starred) “Powerful . . . Kunzru does an excellent job of layering the atmosphere with fear and disquietude at every turning point. This nightmarish allegory leaves the reader with much to chew on about literature’s role in the battleground of ideas.” — Publishers Weekly HARI KUNZRU is the author of five previous novels: White Tears, The Impressionist, Transmission, My Revolutions, and Gods Without Men . His work has been translated into twenty-one languages, and his short stories and journalism have appeared in many publications, including The New York Times, The Guardian, and The New Yorker . He is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the New York Public Library, and the American Academy in Berlin. He lives in Brooklyn, New York. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. I think it is possible to track the onset of middle age exactly. It is the moment when you examine your life and instead of a field of possibility opening out, an increase in scope, you have a sense of waking from sleep or being washed up onshore, newly conscious of your surroundings. So this is where I am, you say to yourself. This is what I have become. It is when you first understand that your condition—physically, intellectually, socially, financially—is not absolutely mutable, that what has already happened will, to a great extent, determine the rest of the story. What you have done cannot be undone, and much of what you have been putting off for “later” will never get done at all. In short, your time is a finite and dwindling resource. From this moment on, whatever you are doing, whatever joy or intensity or whirl of pleasure you may experience, you will never shake the almost-imperceptible sensation that you are traveling on a gentle downward slope into darkness.xa0For me this realization of mortality took place, conventionally enough, beside my sleeping wife at home in our apartment in Brooklyn. As I lay awake, listening to her breathing, I knew that my strength and ingenuity had their limits. I could foresee a time when I would need to rest. How I’d got there was a source of amazement to me, the chain of events that had led me to that slightly overheated bedroom, to a woman who, had things turned out differently, I might never have met, or recognized as the person I wanted to spend my life with. After five years of marriage I was still in love with Rei and she was still in love with me. All that was settled, a happy fact. Our three-year-old daughter was asleep in the next room.xa0Our very happiness made me uneasy. It was a perverse reaction, I knew. I was like a miser, fretting about his emotional hoard. Yet the mental rats running round my bedroom, round my child’s bedroom, had something real behind them. It was a time when the media was full of images of children hurt and displaced by war. I frequently found myself hunched over my laptop, my eyes welling with tears. I was distressed by what I saw, but also haunted by a more selfish question: If the world changed, would I be able to protect my family? Could I scale the fence with my little girl on my shoulders? Would I be able to keep hold of my wife’s hand as the rubber boat overturned? Our life together was fragile. One day something would break. One of us would have an accident, one of us would fall sick, or else the world would slide further into war and chaos, engulfing us, as it had so many other families.xa0In most respects, I had little to complain about. I lived in one of the great cities of the world. Save for a few minor ailments I was physically healthy. And I was loved, which protected me from some of the more destructive consequences of a so-called midlife crisis. I had friends who, without warning, embarked on absurd sexual affairs, or in one case developed a ruinous crack habit that he kept hidden from everyone until he was arrested at 3 a.m. in Elizabeth, New Jersey, smoking behind the wheel of his parked car. I was not about to fuck the nanny or gamble away our savings, but at the same time, I knew there was something profoundly but subtly wrong, some urgent question I had to answer, that concerned me in isolation and couldn’t be solved by waking Rei or going on the internet or padding barefoot into the bathroom and swallowing a sleeping pill. It concerned the foundation for things, beliefs I had spent much of my life writing and thinking about, the various claims I made for myself in the world. And coincidentally or not, it arrived at a time when I was about to go away. One reason I was awake, worrying about money and climate change and Macedonian border guards, was that an airport transfer was booked for five in the morning. I never sleep well on the night before I have to travel. I’m always nervous that I’ll oversleep and miss my plane.xa0xa0xa0Tired and preoccupied, I arrived in Berlin the next day to begin a three-month residency at the Deuter Center, out in the far western suburb of Wannsee. It was just after New Year, and the wheels of the taxi crunched down the driveway over a thin crust of snow. As I caught my first glimpse of the villa, emerging from behind a curtain of white-frosted pines, it seemed like the precise objective correlative of my emotional state, a house that I recognized from some deep and melancholy place inside myself. It was large but unremarkable, a sober construction with a sharply pitched gray-tiled roof and a pale façade pierced by rows of tall windows. Its only peculiarity was a modern annex that extended out from one side, a glass cube that seemed to function as an office.xa0I paid the driver and staggered up the front steps with my bags. Before I could ring the bell, there was a buzzing sound, and the door opened onto a large, echoing hallway. I stepped through it, feeling like a fairytale prince entering the ogre’s castle, but instead of a sleeping princess, I was greeted by a jovial porter in English country tweeds. His manner seemed at odds with the somber surroundings. He positively twinkled with warmth, his eyes wide and his chest puffed out, apparently with the pleasure induced by my arrival. Had my journey been smooth? Would I like some coffee? A folder had been prepared with a keycard and various documents requiring my signature. The director and the rest of the staff were looking forward to meeting me. In the meantime, I would find mineral water and towels in my room. If I needed anything, anything at all, I had only to ask. I assured him that the only thing I wanted was to change and take a look at my study.xa0Of course, he said. Please allow me to help you with your cases.xa0We took an elevator to the third floor, where he showed me into a sort of luxurious garret. The space was clean and bright and modern, with pine furniture and crisp white sheets on a bed tucked under the sloping beams of the roof. The heaters were sleek rectangular grids, the windows double-glazed. In one corner was a little kitchenette, with a hot plate and a fridge. A door led through to a well-appointed bathroom. Despite these conveniences, the room had an austere quality that I found pleasing. It was a place to work, to contemplate.xa0When the Deuter Center wrote to offer me the fellowship, I immediately pictured myself as the “poor poet” in a nineteenth-century painting I’d once seen on a visit to Munich. The poet sits up in bed wearing a nightcap edged in gold thread, with gold-rimmed spectacles perched on his nose and a quill clamped between his jaws like a pirate’s cutlass. His attic room has holes in the windows and is obviously cold, since he’s bundled up in an old dressing gown, patched at one elbow. He’s been using pages from his own work to light the fire, which has now gone out. His possessions are meager, a hat, a coat and a stick, a candle stub in a bottle, a wash basin, a threadbare towel, a torn umbrella hanging from the ceiling. Around him books are piled upon books. Flat against his raised knees he holds a manuscript and with his free hand he makes a strange “OK” gesture, pressing thumb against forefinger. Is he scanning a verse? Crushing a bedbug? Or is he making a hole? Could he possibly be contemplating absence, the meaninglessness of existence, nothingness, the void? The poet doesn’t care about his physical surroundings, or if he does, he’s making the best of things. He is absorbed in his artistic labor. That was how I wanted to be, who I wanted to be, at least for a while.xa0The Center’s full name was the Deuter Center for Social and Cultural Research. Its founder, an industrialist with a utopian streak, had endowed it with some minor part of a fortune made during the years of the postwar economic miracle, with the aim of fostering what he airily called “the full potential of the individual human spirit.” In practical terms, this meant that throughout the year a floating population of writers and scholars was in residence at the Deuter family’s old lakeside villa, catered to by a staff of librarians, cleaners, cooks and computer technicians, all dedicated to promoting an atmosphere in which the fellows could achieve as much work as possible, without being burdened by the practical aspects of daily existence.xa0I was what they call an “independent scholar.” I had an adjunct gig at a university, but it was in a Creative Writing department, and I tried not to think about it except when it was actually happening to me, when I was sitting in a seminar room, pinned by the hollow stares of a dozen debt-ridden graduate students awaiting instruction. What I wrote was published by magazines and commercial publishers, not peer-reviewed journals. Academics found me vaguely disreputable, and I suppose I was. I’ve never been much for disciplinary boundaries. I’m interested in what I’m interested in. Five years before my invitation to Berlin I had published a book about taste, in which I’d argued (not very insistently) that it was intrinsic to human identity. This was barely a thesis, more a sort of bright shiny thing that kept the reader meandering along as I strung together some thoughts on literature, music, cinema and politics. It wasn’t the book I was supposed to be writing, an ambitious work in which I intended to make a definitive case for the revolutionary potential of the arts. The taste book sort of drifted out of me, first as a distraction from the notebooks I was filling with quotations and ideas for my definitive case for the revolutionary potential of the arts, then as a distraction from the creeping realization that I really had no definitive case to make at all, or even a provisional one. I had no clue why anyone should care about the arts, let alone be spurred by them to revolution. I cared about art, but I was essentially a waster, and throughout my life other people had never liked the things I did. The only political slogan that had ever really moved me was Ne travaillez jamais and the attempt to live that out had run into the predictable obstacles. The trouble is there’s no outside, nowhere for the disaffected to go. Refusal is meaningful if conducted en masse, but most people seem to want to cozy up to anyone with the slightest bit of power, and nothing is more scary than being left at the front when a crowd melts away behind you. Why, after all this time was the “general reader” suddenly going to find me persuasive? Why would I even want to persuade him or her? What would starting an argument achieve? If I wanted a fight, all I had to do was look at my phone. So I kept my head down and wrote my distracted essays.xa0I’d been a freelance writer since I was twenty-three. It is a ridiculous thing to do. It’s time-consuming and poorly paid. You live on your nerves. Sure, you can lie on the couch if you want, but eventually you will starve. I was in despair because I’d wasted so much time on the revolution book, and I’d just got together with Rei and needed money to make things happen for us, and suddenly I couldn’t summon the energy for the pretensions of a system, so I just wrote about some things I liked, things that made me happy, and my exhaustion must have transmitted itself in some positive manner onto the page—I am the first to admit that I’m usually a hectoring and difficult writer, given to obscurity and tortuous sentences— because a publisher offered me a contract and along with it a way out, a plausible excuse for shelving the impossible revolutionary art project, smothering the damn thing with a pillow. A mercy killing would otherwise have been embarrassing, since I’d been talking about the book for years, doing panel discussions and think-pieces and sounding off at parties. I finished the little taste book fairly quickly, and unlike my previous work, it sold. You see, said my agent, all you had to do was stop battering people over the head.xa0I did the things you do when you have a successful book. I gave interviews. I accepted invitations to festivals and conferences. Translations were sold. People bought me dinner. Then, gradually, my editor began to inquire about what I was doing next. Mostly what I was doing was getting married and moving apartments and having a baby and not sleeping and realizing that a successful book is not the same thing, financially, as a successful film or a successful song, and writing a couple of prestigious but underpaid magazine essays and agreeing to teach another class and still not sleeping much, but more than before, though still not enough to find it easy to write without self-medicating. I knew I needed to publish again, as soon as possible, but somehow the prospect of completing (or even seriously beginning) a manuscript seemed to recede in front of me. Just when things were getting really tricky, I came to the attention of whatever board or jury awarded the Deuter fellowships. I received a letter from Berlin on pleasingly heavy stationery, inviting me to apply and strongly hinting that I would receive preferential treatment if I did. And so it turned out. I begged for references from the most prestigious writers I knew, and some months later a second letter arrived, informing me that I’d been successful. Three months. Three months of peace. Read more

Features & Highlights

- ONE OF

- THE

- NEW YORK TIMES

- 'S 100 NOTABLE BOOKS OF 2020ONE OF NPR's BEST BOOKS OF 2020ONE OF THE A.V. CLUB'S 15 FAVORITE BOOKS OF 2020From the widely acclaimed author of

- White Tears,

- a bold new novel about searching for order in a world that frames madness as truth.

- After receiving a prestigious writing fellowship in Germany, the narrator of

- Red Pill

- arrives in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee and struggles to accomplish anything at all. Instead of working on the book he has proposed to write, he takes long walks and binge-watches

- Blue Lives

- --a violent cop show that becomes weirdly compelling in its bleak, Darwinian view of life--and soon begins to wonder if his writing has any value at all. Wannsee is a place full of ghosts: Across the lake, the narrator can see the villa where the Nazis planned the Final Solution, and in his walks he passes the grave of the Romantic writer Heinrich von Kleist, who killed himself after deciding that "no happiness was possible here on earth." When some friends drag him to a party where he meets Anton, the creator of

- Blue Lives

- , the narrator begins to believe that the two of them are involved in a cosmic battle, and that Anton is "red-pilling" his viewers--turning them toward an ugly, alt-rightish worldview--ultimately forcing the narrator to wonder if he is losing his mind.