Description

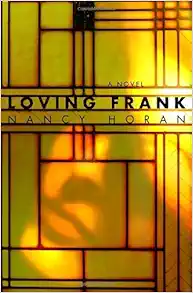

Amazon Significant Seven, August 2007 : It's a rare treasure to find a historically imagined novel that is at once fully versed in the facts and unafraid of weaving those truths into a story that dares to explore the unanswered questions. Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah Cheney's love story is--as many early reviews of Loving Frank have noted--little-known and often dismissed as scandal. In Nancy Horan's skillful hands, however, what you get is two fully realized people, entirely, irrepressibly, in love. Together, Frank and Mamah are a wholly modern portrait, and while you can easily imagine them in the here and now, it's their presence in the world of early 20th century America that shades how authentic and, ultimately, tragic their story is. Mamah's bright, earnest spirit is particularly tender in the context of her time and place, which afforded her little opportunity to realize the intellectual life for which she yearned. Loving Frank is a remarkable literary achievement, tenderly acute and even-handed in even the most heartbreaking moments, and an auspicious debut from a writer to watch. --Anne Bartholomew From Publishers Weekly Horan's ambitious first novel is a fictionalization of the life of Mamah Borthwick Cheney, best known as the woman who wrecked Frank Lloyd Wright's first marriage. Despite the title, this is not a romance, but a portrayal of an independent, educated woman at odds with the restrictions of the early 20th century. Frank and Mamah, both married and with children, met when Mamah's husband, Edwin, commissioned Frank to design a house. Their affair became the stuff of headlines when they left their families to live and travel together, going first to Germany, where Mamah found rewarding work doing scholarly translations of Swedish feminist Ellen Key's books. Frank and Mamah eventually settled in Wisconsin, where they were hounded by a scandal-hungry press, with tragic repercussions. Horan puts considerable effort into recreating Frank's vibrant, overwhelming personality, but her primary interest is in Mamah, who pursued her intellectual interests and love for Frank at great personal cost. As is often the case when a life story is novelized, historical fact inconveniently intrudes: Mamah's life is cut short in the most unexpected and violent of ways, leaving the narrative to crawl toward a startlingly quiet conclusion. Nevertheless, this spirited novel brings Mamah the attention she deserves as an intellectual and feminist. (Aug.) Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. From The New Yorker In 1904, Frank Lloyd Wright started work on a house for an Oak Park couple, Edwin and Mamah Cheney, and, before long, he and Mamah had begun a scandalous affair. In her first novel, Horan, viewing the relationship from Mamahx92s perspective, does well to avoid serving up a bodice-ripper for the smart set. If anything, she cleaves too faithfully to the sources, occasionally giving her story the feel of a dissertation masquerading as a novel. But she succeeds in conveying the emotional center of her protagonist, whom she paints as a proto-feminist, an educated woman fettered by the role of bourgeois matriarch. Horan best evokes Mamahx92s troubled personality by means of delicately rendered reflections on the power of the natural world, from which her lover drew inspiration: watching her children rapturously observe a squirrel as it pulls apart wheat buds or taking pride in the way the house that Wright built for them in Wisconsin frames the landscape. Copyright © 2007 Click here to subscribe to The New Yorker From Bookmarks Magazine Frank Lloyd Wright never once mentioned Mamah Cheney in his letters or autobiography; still, Nancy Horan managed to extrapolate the love affair from newspaper accounts and Mamah's letters to Ellen Key. If Loving Frank didn't hew so closely to the facts, it would read almost like a bodice ripper. Instead, it realistically depicts the opportunities and repercussions of individuals living outside of society's mores and captures the cultural and artistic philosophies of the time. While Horan reveals Wright's hubris and Mamah's intellectual selfishness, the critics, strangely enough, find both endearing. If their love affair carries a "whiff of the Hallmark section" ( Christian Science Monitor ) or clumsily integrates cultural icons into the narrative, these are minor complaints in this compelling story. Copyright © 2004 Phillips & Nelson Media, Inc. From Booklist In the early 1900s, married architect Frank Lloyd Wright eloped to Europe with the wife of one of his clients. The scandal rocked the suburb of Oak Park, Illinois. Years later, Mamah Cheney, the other half of the scandalous couple, was brutally murdered at Wright's Talliesen retreat. Horan blends fact and fiction to try to make the century-old scandal relevant to modern readers. Today Cheney and Wright would have little trouble obtaining divorces and would probably not be pursued by the press. However, their feelings of confusion and doubt about leaving their spouses and children would most likely remain the same. The novel has something for everyonex97a romance, a history of architecture, and a philosophical and political debate on the role of women. What is missing is any sort of note explaining which parts of the novel are based on fact and which are imagined. This is essential in a novel dealing with real people who lived so recently. Block, Marta Segal Advance praise for Loving Frank“This graceful, assured first novel tells the remarkable story of the long-lived affair between Frank Lloyd Wright, a passionate and impossible figure, and Mamah Cheney, a married woman whom Wright beguiled and led beyond the restraint of convention. It is engrossing, provocative reading.”–Scott Turow“It takes great courage to write a novel about historical people, and in particular to give voice to someone as mythic as Frank Lloyd Wright. This beautifully written novel about Mamah Cheney and Frank Lloyd Wright’s love affair is vivid and intelligent, unsentimental and compassionate.”–Jane Hamilton“I admire this novel, adore this novel, for so many reasons: The intelligence and lyricism of the prose. The attention to period detail. The epic proportions of this most fascinating love story. Mamah Cheney has been in my head and heart and soul since reading this book; I doubt she’ll ever leave.”–Elizabeth Berg“Loving Frank is one of those novels that takes over your life. It’s mesmerizing and fascinating–filled with complex characters, deep passions, tactile descriptions of astonishing architecture, and the colorful immediacy of daily life a hundred years ago–all gathered into a story that unfolds with riveting urgency.”–Lauren Belfer Nancy Horan, a former journalist and longtime resident of Oak Park, Illinois, now lives and writes on an island in Puget Sound. From The Washington Post Reviewed By Meg Wolitzer Good ideas for novels sometimes spring nearly fully formed from life. Such is the case with Nancy Horan's Loving Frank, which details Frank Lloyd Wright's passionate affair with a woman named Mamah Cheney; both of them left their family to be together, creating a Chicago scandal that eventually ended in inexplicable violence. It's easy to see why Horan, a former journalist and resident of Oak Park, Ill. -- where Wright was first hired to design a house for Cheney and her husband and which is home to the largest collection of Wright architecture -- found this an excellent subject. Not only are the characters memorable, the buildings are, too. Of course, like all writers of historical fiction, Horan is pinned to the whims and limits of history, which by nature can create a "story" that might easily take undramatic paths or turns. But Horan doesn't seem unduly constrained by the parameters of hard fact, and for long stretches her novel is engaging and exciting. Wright comes across as ardent, visionary and erratic, while Mamah (pronounced May-mah) is a complex person with modern ideas about women's roles in the world. In her diary, Mamah writes out a quote from Charlotte Perkins Gilman: "It is not sufficient to be a mother: an oyster can be a mother." While it might have been hard even for an oyster to be a mother while conducting a love affair with Frank Lloyd Wright, Mamah eventually sees no way to be with him but to abandon her children: "Mamah spoke slowly. 'Now, listen carefully. I'm going to leave tomorrow to go on a trip to Europe. You will stay here with the Browns until Papa arrives in a couple of days. I'm going on a small vacation.' "John burst into tears. 'I thought we were on one.' "Mamah's heart sank. 'One just for me,' she said, struggling to stay calm. . . . Mamah lay down on the bed and pulled their small curled bodies toward her, listening as John's weeping gave way to a soft snore." Horan takes pains to convey her protagonist's maternal guilt and ambivalence, but she also has the children haunt the story like inconvenient, pathetic ghosts. The novel belongs to the feminist genre not only in its depiction of a woman's conflicting desires for love and motherhood and a central role in society, but also through its sophisticated -- and welcome -- focus on the topic of feminism itself. As Mamah says to a friend: "All the talk revolves around getting the vote. That should go without saying. There's so much more personal freedom to gain beyond that. Yet women are part of the problem. We plan dinner parties and make flowers out of crepe paper. Too many of us make small lives for ourselves.' " Mamah wants a big life; for a while she is so captivated by the writings of Swedish writer and philosopher Ellen Key, a leader in what was then referred to as "the Woman Movement," that she becomes her translator. Mamah is as ardent about rights and freedoms as she is about her lover, to whom her thoughts always inevitably circle back: " 'Frank has an immense soul. He's so . . .' She smiled to herself. 'He's incredibly gentle. Yet very manly and gallant. Some people think he's a colossal egoist, but he's brilliant, and he hates false modesty.' " Together Mamah and Frank go off on their European jaunt, which includes appealing period details: "She would walk until her feet were screaming, then rest in cafés where artists buzzed about Modernism at the tables around her." Horan can be a very witty writer; at one point later in the book, she has Frank swatting flies with avidity, naming them before he kills them after critics who once gave him bad reviews: " 'Harriet Monroe!' Whack." But she makes a couple of historically rooted narrative choices that are perplexingly on-the-nose. In a critical scene, Wright says, " 'I'd like to call it Taliesin, if it's all right with you. Do you know Richard Hovey's play Taliesin? About the Welsh bard who was part of King Arthur's court? He was a truth-seeker and a prophet, Taliesin was. His name meant 'shining brow.' I think it's quite appropriate.'" 'Taliesin.' She tried the word in her mouth as she studied the house in the distance." Historical novels sometimes bump right up against the problem of how to render moments that foreshadow events of great significance. In choosing to dwell on the naming of Taliesin, in this instance, Horan gives the moment a nudge and a self-conscious emphasis. It would have been subtler and more effective to refer to the naming of the house in passing, and instead to focus on another, more muted moment of intimacy involving the creation of Taliesin. Loving Frank is a novel of impressive scope and ambition. Like her characters, Horan is going for something big and lasting here, and that is to be admired. In writing about tenderness between lovers or describing a physical setting, she uses prose that is is knowing and natural. At other times, she allows us a glimpse of the hand of fact guiding the hand of art, taking it places where it might not necessarily have chosen to go. Copyright 2007, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. 1907Chapter 1••Mamah Cheney sidled up to the Studebaker and put her hand sideways on the crank. She had started the thing a hundred times before, but she still heard Edwin’s words whenever she grabbed on to the handle. Leave your thumb out. If you don’t, the crank can fly back and take your thumb right off. She churned with a fury now, but no sputter came from beneath the car’s hood. Crunching across old snow to the driver’s side, she checked the throttle and ignition, then returned to the handle and cranked again. Still nothing. A few teasing snowflakes floated under her hat rim and onto her face. She studied the sky, then set out from her house on foot toward the library.It was a bitterly cold end-of-March day, and Chicago Avenue was a river of frozen slush. Mamah navigated her way through steaming horse droppings, the hem of her black coat lifted high. Three blocks west, at Oak Park Avenue, she leaped onto the wooden sidewalk and hurried south as the wet snow grew dense.By the time she reached the library, her toes were frozen stumps, and her coat was nearly white. She raced up the steps, then stopped at the door of the lecture hall to catch her breath. Inside, a crowd of women listened intently as the president of the Nineteenth Century Woman’s Club read her introduction.“Is there a woman among us who is not confronted—almost daily—by some choice regarding how to ornament her home?” The president looked over her spectacles at the audience. “Or, dare I say, herself?” Still panting, Mamah slipped into a seat in the last row and flung off her coat. All around her, the faint smell of camphor fumes wafted from wet furs slung across chair backs. “Our guest speaker today needs no introduction . . .”Mamah was aware, then, of a hush spreading from the back rows forward as a figure, his black cape whipping like a sail, dashed up the middle aisle. She saw him toss the cape first, then his wide-brimmed hat, onto a chair beside the lectern.“Modern ornamentation is a burlesque of the beautiful, as pitiful as it is costly.” Frank Lloyd Wright’s voice echoed through the cavernous hall. Mamah craned her neck, trying to see around and above the hats in front of her that bobbed like cakes on platters. Impulsively, she stuffed her coat beneath her bottom to get a better view.“The measure of a man’s culture is the measure of his appreciation,” he said. “We are ourselves what we appreciate and no more.”She could see that there was something different about him. His hair was shorter. Had he lost weight? She studied the narrow belted waist of his Norfolk jacket. No, he looked healthy, as always. His eyes were merry in his grave, boyish face.“We are living today encrusted with dead things,” he was saying, “forms from which the soul is gone. And we are devoted to them, trying to get joy out of them, trying to believe them still potent.”Frank stepped down from the platform and stood close to the front row. His hands were open and moving now, his voice so gentle he might have been speaking to a crowd of children. She knew the message so well. He had spoken nearly the same words to her when she first met him at his studio. Ornament is not about prettifying the outside of something, he was saying. It should possess “fitness, proportion, harmony, the result of all of which is repose.”The word “repose” floated in the air as Frank looked around at the women. He seemed to be taking measure of them, as a preacher might.“Birds and flowers on hats . . .” he continued. Mamah felt a kind of guilty pleasure when she realized that he was pressing on with the point. He was going to punish them for their bad taste before he saved them.Her eyes darted around at the plumes and bows bobbing in front of her, then rested on one ersatz bluebird clinging to a hatband. She leaned sideways, trying to see the faces of the women in front of her.She heard Frank say “imitation” and “counterfeit” before silence fell once again.A radiator rattled. Someone coughed. Then a pair of hands began clapping, and in a moment a hundred others joined in until applause thundered against the walls.Mamah choked back a laugh. Frank Lloyd Wright was converting them—almost to the woman—before her very eyes. For all she knew five minutes ago, they could just as well have booed. Now the room had the feeling of a revival tent. They were getting his religion, throwing away their crutches. Every one of them thought his disparaging remarks were aimed at someone else. She imagined the women racing home to strip their overstuffed armchairs of antimacassars and to fill vases with whatever dead weeds they could find still poking up through the snow.Mamah stood. She moved slowly as she bundled up in her coat, slid on the tight kid gloves, tucked strands of wavy dark hair under her damp felt hat. She had a clear view of Frank beaming at the audience. She lingered there in the last row, blood pulsing in her neck, all the while watching his eyes, watching to see if they would meet hers. She smiled broadly and thought she saw a glimmer of recognition, a softening around his mouth, but the next moment doubted she had seen it at all.Frank was gesturing to the front row, and the familiar red hair of Catherine Wright emerged from the audience. Catherine walked to the front and stood beside her husband, her freckled face glowing. His arm was around her back.Mamah sank down in her chair. Heat filled up the inside of her coat.On her other side, an old woman rose from her seat. “Claptrap,” she muttered, pushing past Mamah’s knees. “Just another little man in a big hat.”Minutes later, out in the hallway, a cluster of women surrounded Frank. Mamah moved slowly with the crowd as people shuffled toward the staircase.“May-mah!” he called when he spotted her. He pushed his way over to where she stood. “How are you, my friend?” He grasped her right hand, gently pulled her out of the crowd into a corner.“We’ve meant to call you,” she said. “Edwin keeps asking when we’re going to start that garage.”His eyes passed over her face. “Will you be home tomorrow? Say eleven?”“I will. Unfortunately, Ed’s not going to be there. But you and I can talk about it.”A smile broke across his face. She felt his hands squeeze down on hers. “I’ve missed our talks,” he said softly.She lowered her eyes. “So have I.”On her walk home, the snow stopped. She paused on the sidewalk to look at her house. Tiny iridescent squares in the stained-glass windows glinted back the late-afternoon sun. She remembered standing in this very spot three years ago, during an open house she and Ed had given after they’d moved in. Women had been sitting along the terrace wall, gazing out toward the street, calling to their children, their faces lit like a row of moons. It had struck Mamah then that her low-slung house looked as small as a raft beside the steamerlike Victorian next door. But what a spectacular raft, with the “Maple Leaf Rag” drifting out of its front doors, and people draped along its edges.Edwin had noticed her standing on the sidewalk and come to put his arm around her. “We got ourselves a good times house, didn’t we?” he’d said. His face was beaming that day, so full of pride and the excitement of a new beginning. For Mamah, though, the housewarming had felt like the end of something extraordinary.“Out walking in a snowstorm, were you?” Their nanny’s voice stirred Mamah, who lay on the living room sofa, her feet propped on the rolled arm. “I know, Louise, I know,” she mumbled. “Do you want a toddy for the cold you’re about to get?”“I’ll take it. Where is John?”“Next door with Ellis. I’ll get him home.”“Send him in to me when he’s back. And turn on the lights, will you, please?”Louise was heavy and slow, though she wasn’t much older than Mamah. She had been with them since John was a year old—a childless Irish nurse born to mother children. She switched on the stained-glass sconces and lumbered out.When she closed her eyes again, Mamah winced at the image of herself a few hours earlier. She had behaved like a madwoman, cranking the car until her arm ached, then racing on foot through snow and ice to get a glimpse of Frank, as if she had no choice.Once, when Edwin was teaching her how to start the car, he had told her about a fellow who leaned in too close. The man was smashed in the jaw by the crank and died later from infection.Mamah sat up abruptly and shook her head as if she had water in an ear. In the morning I’ll call Frank to cancel.Within moments, though, she was laughing at herself. Good Lord. It’s only a garage. Read more

Features & Highlights

- I have been standing on the side of life, watching it float by. I want to swim in the river. I want to feel the current.

- So writes Mamah Borthwick Cheney in her diary as she struggles to justify her clandestine love affair with Frank Lloyd Wright. Four years earlier, in 1903, Mamah and her husband, Edwin, had commissioned the renowned architect to design a new home for them. During the construction of the house, a powerful attraction developed between Mamah and Frank, and in time the lovers, each married with children, embarked on a course that would shock Chicago society and forever change their lives. In this ambitious debut novel, fact and fiction blend together brilliantly. While scholars have largely relegated Mamah to a footnote in the life of America’s greatest architect, author Nancy Horan gives full weight to their dramatic love story and illuminates Cheney’s profound influence on Wright. Drawing on years of research, Horan weaves little-known facts into a compelling narrative, vividly portraying the conflicts and struggles of a woman forced to choose between the roles of mother, wife, lover, and intellectual. Horan’s Mamah is a woman seeking to find her own place, her own creative calling in the world. Mamah’s is an unforgettable journey marked by choices that reshape her notions of love and responsibility, leading inexorably ultimately lead to this novel’s stunning conclusion. Elegantly written and remarkably rich in detail,

- Loving Frank

- is a fitting tribute to a courageous woman, a national icon, and their timeless love story.

- Advance praise for

- Loving Frank:

- “

- Loving Frank

- is one of those novels that takes over your life. It’s mesmerizing and fascinating–filled with complex characters, deep passions, tactile descriptions of astonishing architecture, and the colorful immediacy of daily life a hundred years ago–all gathered into a story that unfolds with riveting urgency.”–Lauren Belfer, author of

- City of Light

- “This graceful, assured first novel tells the remarkable story of the long-lived affair between Frank Lloyd Wright, a passionate and impossible figure, and Mamah Cheney, a married woman whom Wright beguiled and led beyond the restraint of convention. It is engrossing, provocative reading.”——Scott Turow“It takes great courage to write a novel about historical people, and in particular to give voice to someone as mythic as Frank Lloyd Wright. This beautifully written novel about Mamah Cheney and Frank Lloyd Wright’s love affair is vivid and intelligent, unsentimental and compassionate.”——Jane Hamilton“I admire this novel, adore this novel, for so many reasons: The intelligence and lyricism of the prose. The attention to period detail. The epic proportions of this most fascinating love story. Mamah Cheney has been in my head and heart and soul since reading this book; I doubt she’ll ever leave.”–Elizabeth Berg