Description

Review “Shocking. . . . So exciting. . . . Readers will find themselves simply turning the pages . . . as if they were lost in the exciting adventures of a Victorian James Bond. . . . He is . . . the stuff of legend.”– The Washington Post Book World “A novelistic gallop through history and imagination. . . . Fraser can easily juggle Conan Doyle and Holmes, Fleming and Bond, Wodehouse and Wooster, and Chandler and Marlowe.”– Vanity Fair “Genius. . .one of the literary wonders of the age: historical pastiche raised to such dizzy heights that you forget that it is pastiche and savour it as new-minted fiction.”– The Telegraph “As fine a contribution to history and literature as you could desire. . . .filled with peril, astonishing escapes and sexual escapades. . . brilliant.”– The Boston Globe About the Author George MacDonald Fraser was born in England and educated in Scotland. He served in a Highland regiment in India, Africa, and the Middle East. In addition to his books, he has written screenplays, including The Three Musketeers , The Four Musketeers , and the James Bond film Octopussy . He died in 2008. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. “Half a million in silver, did you say?” “In Maria Theresa dollars. Worth a hundred thou’ in quids.” He held up a gleaming coin, broad as a crown, with the old girl double-chinned on one side and the Austrian arms on t’other. “Dam’ disinheritin’ old bitch, what? Mind, they say she was a plum in her youth, blonde and buxom, just your sort, Flashy—” “Ne’er mind my sort. The cash must reach this place in Africa within four weeks? And the chap who was to have escorted it is laid up in Venice with yellow jack?” “Or the clap, or the sailor’s itch, or heaven knows what.” He spun the coin, grinning foxy-like. “You’ve changed your mind, haven’t you? You’re game to do it yourself! Good old Flash!” “Don’t rush your fences, Speed, my boy. When’s it due to be shipped out?” “Wednesday. Lloyd packet to Alexandria. But with Sturgess comin’ all over yellow in Venice, that won’t do, and there ain’t another Alex boat for a fortnight—far too late, and the Embassy’ll run my guts up the flagpole, as though ’twas my fault, confound ’em—” “Aye, it’s hell in the diplomatic. Well, tell you what, Speed—I’ll ride guard on your dollars to Alex for you, but I ain’t waiting till Wednesday. I want to be clear of this blasted town by dawn tomorrow, so you’d best drum up a steam-launch and crew, and get your precious treasure aboard tonight—where is it just now?” “At the station, the Strada Ferrata—but dammit, Flash, a private charter’ll cost the moon—” “You’ve got Embassy dibs, haven’t you? Then use ’em! The station ain’t spitting distance from the Klutsch mole, and if you get a move on you can have the gelt loaded by midnight. Heavens, man, steam craft and spaghetti sailors are ten a penny in Trieste! If you’re in such a sweat to get the dollars to Africa—” “You may believe it! Let me see . . . quick run to Alex, then train to Cairo and on to Suez—no camel caravans across the desert these days, but you’ll need to hire nigger porters—” “For which you’ll furnish me cash!” He waved a hand. “Sturgess would’ve had to hire ’em, anyway. At Suez one of our Navy sloops’ll take you down the Red Sea—there are shoals of ’em, chasin’ the slavers, and I’ll give you an Embassy order. They’ll have you at Zoola—that’s the port for Abyssinia—by the middle of February, and it can’t take above a week to get the silver up-country to this place called Attegrat. That’s where General Napier will be.” “Napier? Not Bob the Bughunter? What the blazes is he doing in Abyssinia? We haven’t got a station there.” “We have by now, you may be sure!” He was laughing in disbelief. “D’you mean to tell me you haven’t heard? Why, he’s invadin’ the place! With an army from India! The silver is to help fund his campaign, don’t you see? Good God, Flashy, where have you been? Oh, I was forgettin’—Mexico. Dash it, don’t they have newspapers there?” “Hold up, can’t you? Why is he invading?” “To rescue the captives—our consul, envoys, missionaries! They’re held prisoner by this mad cannibal king, and he’s chainin’ ’em, and floggin’ ’em, and kickin’ up no end of a row! Theodore, his name is—and you mean to say you’ve not heard of him? I’ll be damned—why, there’s been uproar in Parliament, our gracious Queen writin’ letters, a penny or more on the income tax—it’s true! Now d’you see why this silver must reach Napier double quick—if it don’t, he’ll be adrift in the middle of nowhere with not a penny to his name, and your old chum Speedicut will be a human sacrifice at the openin’ of the new Foreign Office!” “But why should Napier need Austrian silver? Hasn’t he got any sterling?” “Abyssinian niggers won’t touch it, or anythin’ except Maria Theresas. Purest silver, you see, and Napier must have it for food and forage when he marches up-country to fight his war.” “So it’s a war-chest? You never said a dam’ word about war last night.” “You never gave me a chance, did you? Soon as I told you I was in Dickie’s meadow, with this damned fortune to be shipped and Sturgess in dock, what sympathy did dear old friend Flashy offer? The horse’s laugh, and wished me joy! All for England, home, and the beauteous Elspeth, you were . . . and now,” says he, with that old leery Speedicut look, “all of a sudden, you’re in the dooce of a hurry to oblige . . . What’s up, Flash?” “Not a dam’ thing. I’m sick of Trieste and want away, that’s all!” “And can’t wait a day? You and Hookey Walker!” “Now, see here, Speed, d’ye want me to shift your blasted bullion, or don’t you? Well, I go tonight or not at all, and since this cash is so all-fired important to Napier, your Embassy funds can stand the row for my passage home, too, when the thing’s done! Well, what d’ye say?” “That something is up, no error!” His eyes widened. “I say, the Austrian traps ain’t after you, are they—’cos if they were I daren’t assist your flight, silver or no silver! Dash it, I’m a diplomat—” “Of course ’tain’t the traps! What sort of fellow d’ye think I am? Good God, ha’nt we been chums since boyhood?” “Yes, and it’s ’cos I know what kind of chum you can be that I repeat ‘What’s up, Flash?’ ” He filled my glass and pushed it across. “Come up, old boy! This is old Speed, remember, and you can’t humbug him.” Well, true enough, I couldn’t, and since you, dear reader, may be sharing his curiosity, I’ll tell you what I told him that night in the Hôtel Victoria—not the smartest pub in Trieste, but as a patriotic little minion of our Vienna Embassy, Speedicut was bound to put up there—and it should explain the somewhat cryptic exchanges with which I’ve begun this chapter of my memoirs. If they’ve seemed a mite bewildering you’ll see presently that they were the simplest way of setting out the preliminaries to my tale of the strangest campaign in the whole history of British arms—and that takes in some damned odd affairs, a few of which I’ve borne a reluctant hand in myself. But Abyssinia took the cake, currants and all. Never anything like it, and never will be again. For me, the business began in the summer of ’67, on the day when that almighty idiot, the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, strode out before a Juarista firing squad, unbuttoned his shirt cool as a trout, and cried “Viva Méjico! Viva la independencia! Shoot, soldiers, through the heart!” Which they did, with surprising accuracy for a platoon of dagoes, thereby depriving Mexico of its crowned head and Flashy of his employer and protector. I was an anxious spectator skulking in cover on a rooftop nearby, and when I saw Max take a header into the dust I knew that the time had come for me to slip my cable. You see, I’d been his fairly loyal aide-de-camp in his recent futile struggle against Juarez’s republicans—not a post I’d taken from choice, but I’d been a deserter from the French Foreign Legion at the time. They were polluting Mexico with their presence in those days, supporting Max on behalf of his sponsor, that ghastly louse Louis Napoleon, and I’d been only too glad of the refuge Max had offered me—he’d been under the mistaken impression that I’d saved his life in an ambush at Texatl, poor ass, when in fact I’d been one of Jesús Montero’s gang of ambushers, but we needn’t go into that at the moment. What mattered was that Max had taken me on the strength, and had given the Legion peelers the right about when they’d come clamouring for my unhappy carcase. Then the Frogs cleared out in March of ’67, leaving Max in the lurch with typical Gallic loyalty, but while that removed one menace to my well-being, there remained others from which Max could be no protection, quick or dead—like the Juaristas, who’d rather have strung up a royalist a.d.c. than eaten their dinners, or that persevering old bandolero Jesús Montero, who was bound to find out eventually that I didn’t know where Montezuma’s treasure was. Hell of a place, Mexico, and dam’ confused. But all you need to know for the present is that after Max bought the bullet I’d have joined him in the dead-cart if it hadn’t been for the delectable Princess Agnes Salm-Salm, and the still happily ignorant Jesús. They’d been my associates in a botched attempt to rescue Max on the eve of his execution. We’d failed because (you’ll hardly credit this) the great clown had refused point-blank to escape because it didn’t sort with his imperial dignity, Austro-Hungarian royalty preferring to die rather than go over the wall. Well, hell mend ’em, I say, and if the House of Hapsburg goes to the knackers it won’t be my fault; I’ve done my unwilling best for them, ungrateful bastards. At all events, darling Aggie and greasy Jesus had seen me safe to Vera Cruz, where she had devised the most capital scheme for getting me out of the country. Max having been brother to the Austrian Emperor Franz Josef, his death had caused a sensation in Vienna; they hadn’t done a dam’ thing useful to save his life, but they made up for it with his corpse, sending a warship to ferry it home, with a real live admiral and a great retinue of court reptiles. And since Aggie was the wife of a German princeling, a heroine of the royalist campaign, and handsome as Hebe, they were all over her when we went aboard the Novara frigate at Sacraficios. Admiral Tegethoff, a bluff old sport, all beard and belly, munched her knuckles and gave glad welcome even to the begrimed and ragged peon whom she presented as the hoch und wohlgeboren Oberst Sir Harry Flashman, former aide, champion, and all-round hero of the campaign and the ill-starred attempt to snatch his imperial majesty from the firing squad. “The Emperor’s English right arm, gentlemen!” says Aggie, who was a great hand at the flashing-eyed flourish. “So his majesty called him. Who more fitting to guard his royal master and friend on his last journey home?” Blessed if they could think of anyone fitter, and I was received with polite enthusiasm: the reptiles left off sneering at my beastly peasant appearance and clicked their heels, old Tegethoff stopped just short of embracing me, and I was aware of the awestruck admiration in the wide blue eyes of the enchanting blonde poppet whom he presented as his great-niece, Gertrude von und zum something-or-other. My worldly Aggie noticed it too, and observed afterwards, when we made our adieus at the ship’s rail, that if I looked like a scarecrow I was at least a most romantic one. “The poor little idiot will doubtless break her foolish heart over you en voyage,” says she. “And afterwards wonder what she saw in the so dashing English rascal.” “Jealous of her, princess?” says I, and she burst out laughing. “Of her youth, perhaps—not of her infatuation.” She gave that slantendicular smile that had been driving me wild for months. “Well, not very much. But if I were sixteen again, like her, who knows? Adiós, dear Harry.” And being royally careless of propriety, she kissed me full on the lips before the startled squareheads—and for a delightful moment it was the kiss of the lover she’d never been, which I still count a real conquest. Pity she was so crazy about her husband, I remember thinking, as she waved an elegant hand from her carriage and was gone. After that they towed Max’s coffin out to the ship in a barge and hoisted it inboard, and as the newly appointed escort to his cadaver I was bound to give Tegethoff and his entourage a squint at the deceased, so that they could be sure they’d got the right chap. It was no end of a business, for his Mexican courtiers had done him proud with no fewer than three coffins, one of rosewood, a second of zinc, and the third of cedar, with Max inside the last like one of those Russian dolls. He’d been embalmed, and I must say he looked in capital fettle, bar being a touch yellow and his hair starting to fall out. We screwed him in again, a chaplain said a prayer, and all that remained was to weigh anchor to thunderous salutes from various attendant warships, and for me to remind Tegethoff that a bath and a change of clobber would be in order. I’ve never had any great love for the cabbage-chewers, having been given my bellyful by Bismarck and his gang in the Schleswig-Holstein affair,* and Tegethoff’s party included more than one of the crop-headed schlager-swingers whom I find especially detestable, but I’m bound to say that on that voyage, which lasted from late November ’67 to the middle of January, they couldn’t have been more amiable and hospitable—until the very morning we dropped anchor off Trieste, when Tegethoff discovered that I’d been giving his great-niece a few exercises they don’t usually teach in young ladies’ seminaries. Aggie had been right, you see: the silly chit had gone nutty on me at first sight, and who’s to blame her? Stalwart Flashy all bronzed and war-weary in sombrero and whiskers might well flutter a maiden heart, and if at forty-five I was old enough to be her father, that never stopped an adoring innocent yet, and you may be sure it don’t stop me either. Puppy-fat and golden sausage curls ain’t my style as a rule, but combined with a creamy complexion, parted rosebud lips, and great forget-me-not eyes alight with idiotic worship, they have their attraction. For one thing they awoke blissful memories of Elspeth on that balmy evening when I first rattled her in the bushes by the Clyde. The resemblance was * See Royal Flash. more than physical, for both were brainless, although my darling half-wit is not without a certain native cunning, but what made dear little Fräulein Gertrude specially irresistible was her truly unfathomable ignorance of the more interesting facts of life, and her touching faith in me as a guide and mentor. Her attachment to me on the voyage was treated as something of a joke by Tegethoff’s people, who seemed to regard her as a child still, more fool they, and since her duenna was usually too sea-sick to interfere, we were together a good deal. She was the most artless prattler, and was soon confiding her girlish secrets, dreams, and fears; I learned that her doting great-uncle had brought her on the cruise as a betrothal present, and that on her return to Vienna she was to be married to a most aristocratic swell, a graf no less, whom she had never seen and who was on the brink of the grave, being all of thirty years old. “It is such an honour,” sighs she, “and my duty, Mama says, but how am I to be worthy of it? I know nothing of how to be a wife, much less a great lady. I am too young, and foolish, and . . . and little! He is a great man, a cousin to the Emperor, and I am only a lesser person! How do I know how to please him, or what it is that men like, and who is to tell me?” Yearning, dammit, drowning me in her blue limpid pools, with her fat young juggs heaving like blancmange. Strip off, lie back, and enjoy it, would have been the soundest advice, but I patted her hand, smiled paternally, and said she mustn’t worry her pretty little head, her graf was sure to like her. “Oh, so easy to say!” cries she. “But if he should not? How to win his affection?” She rounded on me eagerly. “If it were you”—and from her soulful flutter she plainly wished it was, sensible girl—“if it were you, how could I best win your heart? How make you . . . oh, admire me, and honour me, and . . . and love me! What would delight you most that I could do?” You may talk about sitting birds, but where a lesser man might have taken swift advantage of that guileless purity, I’m proud to say that I did not. She might be the answer to a lecher’s prayer, but I knew it would take delicate management and patience before we could have her setting to partners in the Calcutta Quadrille. So I went gently to work, indulgent uncle in the first week, brotherly arm about her shoulders in the second, peck on the cheek in the third, touch on the lips at Christmas to make her think, sudden lustful growl and passionate kiss for New Year, meeting her startled-fawn bewilderment with a nice blend of wistful adoration and unholy desire which melted the little simpleton altogether, and bulled her speechless all the way along the Adriatic. Very discreet, mind; a ship’s a small place, and chaste young ladies tend to be excitable the first few times and need to be hushed. Elspeth, and my second wife, Duchess Irma, were like ecstatic banshees, I remember. Unfortunately, she shared another characteristic with Elspeth— she had no more discretion than the town crier, and just as Elspeth had babbled joyfully of our jolly rogering to her elder sister, who had promptly relayed it to her horrified parents, so sweet imbecile Gertrude had confided in her duenna, who had swooned before passing on the glad news to old Tegethoff. This must have been on the very morning we dropped anchor off the Molo St. Carlo at Trieste and I was supervising the lifting of the coffin from below decks, and in the very act of securing Max’s crown and archducal cap to the lid, when Tegethoff damned near fell down the companion, with a couple of aides at his heels trying to restrain him. He was in full fig, cocked hat and ceremonial sword which he was trying to lug out, purple with rage, and bellowing “Verräter! Vergewaltiger! Pirat!”* which summed up things nicely and explained why he was behaving like Attila with apoplexy. One of the aides clung to his sword-arm and hauled him back by main force, while the other, a hulking junkerish brute with scars all over his ugly dial, whipped his glove across my face before dashing it at my feet and stamping off. That was all they * “Traitor! Rapist! Pirate!” had time for just then, what with the barge coming alongside to take Max on shore leave, the Duke of Würtemburg and all the other big guns lined up on the landing stage, the waterfront swathed in black, and muted brass bands playing a cheery Wagnerian air. But I can take a hint, and saw that by the time they’d finished escorting Max to the Vienna train, I had best be in the nearest deep cover, lying doggo. So I let the pall-bearers get their load on deck, waited until the guns of the assembled shipping had started their salutes and Tegethoff and Co. would be safely away, and slunk ashore with a hastily packed valise. The cortège was proceeding along the boulevard beyond the Grand Canal which runs into the heart of the city; solemn music, mobs of chanting clergy, friars carrying crosses, battalions of infantry, and I thought “Hasta la vista, old Max” and hurried up-town to lose myself for a few hours. Tegethoff’s gang would be off to Vienna with the corpse presently, nursing their wrath against me, no doubt, but unable to indulge it, and then I could consider how the devil I was to raise the blunt for a passage to England, for bar a few pesos and Yankee dollars my pockets were to let. Trieste ain’t much of a town unless you’re in trade or banking or some other shady pursuit; Napoleon’s spymaster, Fouché, is buried there, and Richard the Lionheart did time in jail, but the only other excitements are the Tergesteum bazaar and the Corso, which is the main drag between the new and old cities, and you can stare at shop windows and drink coffee to bursting point. At evening I mooched up to the Exchange plaza and into the casino club, where the smart set foregathered and I thought I might run across some sporting rich widow eager for carnal amusement, but I’d barely begun to survey the fashionable throng when I found myself face to face with the last man I’d have thought to meet, my old chum of Rugby and the Cider Cellars, Speedicut, whom I’d barely seen since the night the Minor Club in St. James’s was raided, and we’d fled from the peelers and I’d found refuge in the carriage (and later the bed) of Lola Montez, bless her black heart. That had been all of twenty-five years before, but we knew each other on the instant, and there was great rejoicing, in a wary sort of way, for we’d never been your usual bosom pals, both being leery by nature. So now I learned that he was in the diplomatic, which didn’t surprise me, for he was a born toad-eater with a great gift of genteel sponging and an aversion to work. He was full of woe because, as you’ll already have gathered, he’d brought this fortune in silver down from Vienna for shipment to Abyssinia, and lo! the appointed escort had fallen by the way and he was at his wit’s end to find another—couldn’t go himself, diplomatic duty bound him to Austrian soil, etc., etc. . . . It was at that point that it dawned on him that here was good old Harry, knight of the realm, hero of Crimea and the Mutiny, darling of Horse Guards, and just the chap who could be trusted with a vital mission in his country’s service. Why, I was heaven-sent and no mistake, dear old lad that I was! There wasn’t a hope of touching him for a loan to see me home, for coming of nabob wealth he was as mean as Solomon Levi, but by pretending interest I was able to take a decent dinner off him at the Locanda Granda before telling him, fairly politely, for one hates to offend, what he could do with his cargo of dollars. He howled a bit, but didn’t press me, for he hadn’t really expected me to agree, and we parted on fair terms, he to visit the station to see that his minions were taking care of the doubloons, I to find a cheap bed for the night. And I hadn’t turned the corner before I saw something that had me skipping for the nearest alleyway with my undigested dinner in sudden turmoil. Not twenty yards away across the street, the Austrian lout who’d slapped my face and hurled his challenge at my feet was conferring with two uniformed constables and a bearded villain in a billycock hat with plain-clothes peeler written all over him. And there were two armed troopers in tow as well. Even as I watched them disperse, the officer mounting the steps to the Locanda which I’d just left, the fearful truth was dawning—Tegethoff had left this swine behind to track me down and either hale me to justice as a ravisher of youth (squareheads have the most primitive views about this, as I’d discovered in Munich in ’47 when Bismarck’s bullies interrupted my dalliance with that blubbery slut Baroness Pechmann), or more likely cut me up in a sabre duel. Trieste had suddenly become too hot to hold me—so now you know why a couple of hours later I was in Speedicut’s room at the Victoria, clamouring to be allowed to remove his bullion for him, to Abyssinia or Timbuctoo or any damned place away from Austrian vengeance. In my funk I even conjured up the nightmare thought that if Tegethoff got his hands on me and instituted inquiries, he might easily discover I was a Legion deserter and hand me over to the bloody Frogs, in which case I’d end my days as a slave in their penal battalion in the Sahara. A groundless fear, looking back, but I’m a great one for starting at shadows, as you may know. I didn’t mention this particular phantasm to Speed, but I did tell him all about Gertrude, ’cos that sort of thing was nuts to him, and he was lost in admiration of my behaviour both as amorist and fugitive. “How the blazes you always contrive to slide out o’ harm’s way beats me—aye, often as not with some charmer languishin’ after you! Well, ’twas dam’ lucky for you I was here this time!” “Lucky for both of us. So, now that you know all about my guilty past, d’you still feel like trusting me with your half-million? No fears that I might tool along the coast to Monte Carlo and blue the lot at the wheel?” Put like that, with a wink and a grin, he didn’t care for it above half, but common sense told him I wasn’t going to levant,* and he’d no choice, anyway. So a couple of hours after midnight, there I was at the Klutsch mole, watching Speed’s clerk settle up with the skipper of a neat little smack or yawl or whatever they call ’em, while its crew of Antonios chattered and loafed on * To steal away, abscond. the hatches—even in those days Trieste was more Italian than Austrian—and here came Speed in haste across the deserted plaza from the station, with a squad of Royal Marines from his Embassy wheeling the goods on a hand-cart: scores of little strong-boxes with the locks sealed with the royal arms. There were four of the Bootnecks under a sergeant with a jaw like a pike, all very trim with their Sniders slung; Speed’s dollars would be safe from sea pirates and land banditti with this lot on hand. It may have been my jest about Monte or his natural fear at seeing his precious cargo pass out of his ken, but now that the die was cast Speed had a fit of the doubtfuls; earlier he’d been begging me to come to his rescue, but now he was chewing his lip as they swung the boxes down to the deck with the Eyeties jabbering and the sergeant giving ’em Billingsgate, while I took an easy cheroot at the rail, trying my Italian pidgin on the skipper. “This ain’t a joke, Flash!” says Speed. “It’s bloody serious! You’re carryin’ my career along with those dollars—my good name, dammit!” As if he had one. “Jesus, if anything should go wrong! You will take care, old chap, won’t you? I mean, you’ll do nothin’ wild . . . you know, like . . . like . . .” He broke off, not caring to say “like buggering off to Pago Pago with the loot.” Instead he concluded glumly: “ ’Tain’t insured, you know—not a penny of it!” I assured him that his specie would reach Napier safely in less than four weeks, but he still looked blue and none too eager to hand over the Embassy passport requesting and requiring H.M. servants, civil and military, to speed me on my way, and a letter for Napier, asking him to give me a warrant and funds for my passage home. I shook hands briskly before he could change his mind, and as we shoved off and the skipper spun the wheel and his crew dragged the sail aloft, damned if he wasn’t here again, running along the mole, waving and hollering: “I say, Flash, I forgot to ask you for a receipt!” I told him to forge my signature if it would make him sleep sounder, and his bleating faded on the warm night air as we stood out from the mole, the little vessel heeling over suddenly as the wind cracked in her sail; the skipper bawled commands as the hands scampered barefoot to tail on to the lines, and I looked back at the great brightly lit crescent of the Trieste waterfront and felt a mighty relief, thinking, well, Flashy my boy, that’s another town you’re glad to say good-bye to on short acquaintance, and here’s to a jolly holiday cruise to a new horizon and an old friend, and then hey! for a swift passage home, and Elspeth waiting. Strange, little Gertrude was fading from memory already, but I found myself reflecting that thanks to my tuition her princeling husband would be either delighted or scandalised on his wedding night—possibly both, the lucky fellow. You gather from this that I was in a tranquil, optimistic mood as I set off on my Abyssinian odyssey, ass that I was. You’d ha’ thought, after all I’d seen and suffered in my time, that I’d have remembered all the occasions when I’d set off carefree and unsuspecting along some seemingly primrose path only to go head first into the pit of damnation at t’other end. But you never can tell. I couldn’t foresee, as I stood content in the bow, watching the green fire foaming up from the forefoot, feeling the soft Adriatic breeze on my face, hearing the oaths and laughter of the Jollies and the strangled wailing of some frenzied tenor in the crew—I couldn’t foresee the screaming charge of long-haired warriors swinging their hideous sickle-blades against the Sikh bayonets, or the huge mound of rotting corpses under the precipice at Islamgee, or the ghastly forest of crucifixes at Gondar, or feel the agonising bite of steel bars against my body as I swung caged in the freezing gale above a yawning void, or imagine the ghastly transformation of an urbane, cultivated monarch into a murderous tyrant shrieking with hysterical glee as he slashed and hacked at his bound victims. No, I foresaw none of those horrors, or that amazing unknown country, Prester John’s fabled land of inaccessible mountain barriers and bottomless chasms, and wild, war-loving beautiful folk, into which Napier was to lead such an expedition as had not been seen since Cortes and Pisarro (so Henty says), through impossible hazards and hopeless odds—and somehow lead it out again. A land of mystery and terror and cruelty, and the loveliest women in all Africa . . . a smiling golden nymph in her little leather tunic, teasing me as she sat by a woodland stream plaiting her braids . . . a gaudy barbarian queen lounging on cushions surrounded by her tame lions . . . a tawny young beauty remarking to my captors: “If we feed him into the fire, little by little, he will speak . . .” Aye, it’s an interesting country, Abyssinia. If you’ve read my previous memoirs you’ll know me better than Speedicut did, and won’t share his misgivings about trusting me with a cool half million in silver. Old Flash may be a model of the best vices—lechery, treachery, poltroonery, deceit, and dereliction of duty, all present and correct, as you know, and they’re not the half of it—but larceny ain’t his style at all. Oh, stern necessity may have led to my lifting this and that on occasion, but nothing on the grand scale—why, you may remember I once had the chance to make away with the great Koh-i-noor diamond,* but wasn’t tempted for an instant. If there’s one thing your true-bred coward values, it’s peace of mind, and you can’t have that if you’re a hunted outlaw forever far from home. Also, pocketing a diamond’s one thing, but stacks of strong-boxes weighing God knows what and guarded by five stout lads are a very different palaver. Speed had spoken lightly of a quick trip to Alexandria, but with that pack of dilatory dagoes tacking to and fro and putting about between the heel of Italy and Crete, we must have covered all of two thousand miles, and half the time allotted me to reach Napier had gone before we sighted Egypt. It’s a sand-blown * See Flashman and the Mountain of Light. dunghill at any time, but I was dam’ glad to see it after that dead bore of a voyage—and no dreary haul across the desert in prospect either. The camel journey was a penance I’d endured in the past, but now it was rails all the way from Alex to Suez, by way of Cairo, and what had once taken days of arse-burning discomfort was now a journey of eight hours, thanks to our engineers who’d won the concession in the teeth of frantic French opposition. They were hellish jealous of their great canal, which was then within a year of completion, with gangs of thousands of the unfortunate fellaheen being mercilessly flogged on the last lap, for it was built with slave labour in all but name. We didn’t linger in Alexandria; Egypt’s the last place you want to carry a cargo of valuables, so I made a quick sortie to the Hôtel de l’Europe for a bath and a civilised breakfast while the Marine sergeant drummed up the local donkey drivers to carry the boxes to the station, and then we were rattling away, four hours to Cairo, another four on the express to Suez, and before bed-time I’d presented myself to the port captain and was dining in the Navy mess. Abyssinia was on every lip, and when it was understood that the celebrated Flashy was bringing Napier his war-chest, it was heave and ho with a vengeance. A steam sloop commanded by a cheerful infant named Ballantyne with a sun-peeled nose and a shock of fair hair bleached almost white by the sun was placed at my disposal, his tars hoisted the strong-boxes aboard and stowed them below, the Jollies were crammed into the tiny focsle, and as the sun came up next morning we were thrashing down the Gulf of Suez to the Red Sea proper, having been in and out of Egypt in twenty-four hours, which is a day longer than you’d care to spend there. The Suez gulf isn’t more than ten miles across at its narrowest point, and Ballantyne, who was as full of gas and high spirits as a twenty-year-old with an independent command can be, informed me that this was where the Children of Israel had made their famous crossing in the Exodus, “but it’s all balls and Banbury about the sea being parted and Pharaoh’s army being drowned, you know. There are places where you can walk from Egypt to the Sinai at low tide, and an old Gyppo nigger told me it wasn’t Pharaoh who was chasing ’em, either, but a lot of rascally Bedouin Arabs, and after Moses had got over at low water, the tide came in and the buddoos were drowned and serve ’em right. And there wasn’t a blessed chariot to be seen when the tide went out, so there!” Read more

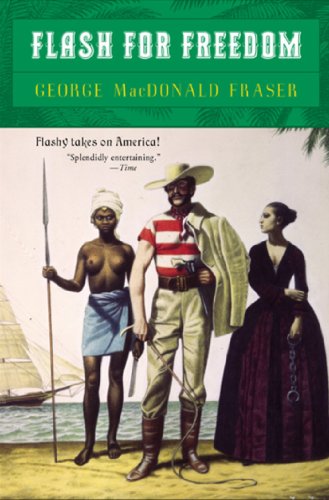

Features & Highlights

- It’s 1868 and Sir Harry Flashman, V.C., arch-cad, amorist, cold-headed soldier, and reluctant hero, is back! Fleeing a chain of vengeful pursuers that includes Mexican bandits, the French Foreign Legion, and the relatives of an infatuated Austrian beauty, Flashy is desperate for somewhere to take cover. So desperate, in fact, that he embarks on a perilous secret intelligence-gathering mission to help free a group of Britons being held captive by a tyrannical Abyssinian king. Along the way, of course, are nightmare castles, brigands, massacres, rebellions, orgies, and the loveliest and most lethal women in Africa, all of which will test the limits of the great bounder’s talents for knavery, amorous intrigue, and survival.

- Flashman on the March—

- the twelfth book in George MacDonald Fraser’s ever-beloved, always scandalous Flashman Papers series--is Flashman and Fraser at their best.