Description

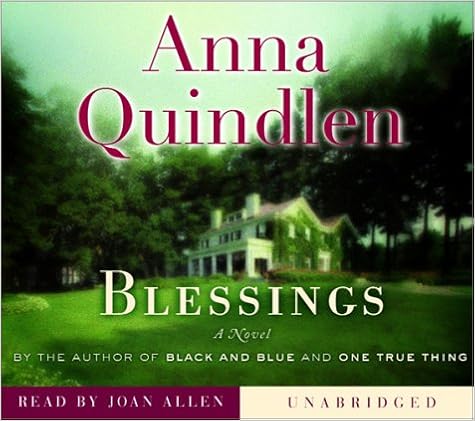

“Spellbinding.”— The New York Times Book Review “In a tale that rings strikingly true, [Anna] Quindlen captures both the beauty and the breathtaking fragility of family life.”— People “We come to love this family, because Quindlen makes their ordinary lives so fascinating, their mundane interactions engaging and important. . . . Never read a book that made you cry? Be prepared for a deluge of tears.”— USA Today “Anna Quindlen’s writing is like knitting; prose that wraps the reader in the warmth and familiarity of domestic life. . . . Then, as in her novels Black and Blue and One True Thing, Quindlen starts to pull at the world she has knitted, and lets it unravel across the pages.”— The Seattle Times “Packs an emotional punch . . . Quindlen succeeds at conveying the transience of everyday worries and the never-ending boundaries of a mother’s love.”— The Washington Post “A wise, closely observed, achingly eloquent book.”—The Huffington Post xa0 “If you pick up Every Last One to read a few pages after dinner, you’ll want to read another chapter, and another and another, until you get to bed late.”—Associated Press xa0 “Quindlen conjures family life from a palette of finely observed details.”— Los Angeles Times “[Quindlen’s] emotional sophistication, and her journalistic eye for authentic dialogue and detail, bring the ring of truth to every page of this heartbreakingly timely novel.”—NPR Anna Quindlen is the author of five bestselling novels ( Rise and Shine, Blessings, Object Lessons, One True Thing, Black and Blue ), and six nonfiction books ( Being Perfect, Loud & Clear, A Short Guide to a Happy Life, Living Out Loud, Thinking Out Loud, How Reading Changed My Life ). She has also written two children's books ( The Tree That Came to Stay, Happily Ever After ). Her New York Times column "Public and Private" won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992. Her column now appears every other week in Newsweek . Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. This is my life: The alarm goes off at five-thirty with the murmuring of a public-radio announcer, telling me that there has been a coup in Chad, a tornado in Texas. My husband stirs briefly next to me, turns over, blinks, and falls back to sleep for another hour. My robe lies at the foot of the bed, printed cotton in the summer, tufted chenille for the cold. The coffeemaker comes on in the kitchen below as I leave the bathroom, go downstairs in bare feet, pause to put away a pair of boots left splayed in the downstairs back hallway and to lift the newspaper from the back step. The umber quarry tiles in the kitchen were a bad choice; they are always cold. I let the dog out of her kennel and put a cup of kibble in her bowl. I hate the early mornings, the suspended animation of the world outside, the veil of black and then the oppressive gray of the horizon along the hills outside the French doors. But it is the only time I can rest without sleeping, think without deciding, speak and hear my own voice. It is the only time I can be alone. Slightly less than an hour each weekday when no one makes demands.Our bedroom is at the end of the hall, and sometimes as I pass I can hear the children breathing, each of them at rest as specific as they are awake. Alex inhales and exhales methodically, evenly, as though he were deep under the blanket of sleep even though he always kicks his covers askew, leaving one long leg, with its faint surgical scars, exposed to the night air. Across the room Max sputters, mutters, turns, and growls out a series of nonsense syllables. For more than a year when he was eleven, Max had a problem with sleepwalking. I would find him washing his hands at the bathroom sink or down in the kitchen, blinking blindly into the open refrigerator. But he stopped after his first summer at sleepaway camp.Ruby croons, one high strangled note with each exhale. When she was younger, I worried that she had asthma. She sleeps on her back most of the time, the covers tucked securely across her chest, her hair fanned out on the pillows. It should be easy for her to slip from beneath the blanket and make her bed, but she never bothers unless I hector her.I sit downstairs with coffee and the paper, staring out the window as my mind whirrs. At six-thirty I hear the shower come on in the master bath. Glen is awake and getting ready for work. At six-forty-five I pull the duvet off Ruby, who snatches it back and curls herself into it, larval, and says, “Ten more minutes.” At seven I lean over, first Alex, then Max, and bury my nose into their necks, beginning to smell the slightly pungent scent of male beneath the sweetness of child. “Okay, okay,” Alex says irritably. Max says nothing, just lurches from bed and begins to pull off an oversized T-shirt as he stumbles into the bathroom.There is a line painted down the center of their room. Two years ago they came to me, at a loose end on a June afternoon, and demanded the right to choose their own colors. I was distracted, and I agreed. They did a neat job, measured carefully, put a tarp on the floor. Alex painted his side light blue, Max lime green. The other mothers say, “You won’t believe what Jonathan”—or Andrew or Peter—“told me about the twins’ room.” Maybe if the boys had been my first children I would have thought it was insane, too, but Ruby broke me in. She has a tower of soda cans against one wall of her bedroom. It is either an environmental statement or just one of those things you do when you are fifteen. Now that she is seventeen she has outgrown it, almost forgotten it, but because I made the mistake of asking early on when she would take it down she never has.I open Ruby’s door, and although it doesn’t make a sound—she has oiled the hinges, I think, probably with baby oil or bath oil or something else nonsensically inappropriate, so we will not hear it creak in the nighttime—she says, “I’m up.” I stand there waiting, because if I take her word for it she will wrap herself in warmth again and fall into the long tunnel of sleep that only teenagers inhabit, halfway to coma or unconsciousness. “Mom, I’m up,” she shouts, and throws the bedclothes aside and begins to bundle her long wavy hair atop her head. “Can I get dressed in peace, please? For a change?” She makes it sound as though I constantly let a bleacher full of spectators gawk as she prepares to meet the day.Only Glen emerges in the least bit cheerful, his suit jacket over one arm. He keeps his white coats at the office. They are professionally cleaned and pressed and smell lovely, like the cleanest of clean laundry. “Doctor Latham” is embroidered in blue script above his heart. From upstairs I can hear the clatter of the cereal into his bowl. He eats the same thing every morning, leaves for work at the same time. He wears either a blue or a yellow shirt, with either a striped tie or one with a small repeating pattern. Occasionally, a grateful patient gives him a tie as a gift, printed with tiny pairs of glasses, an eye chart, or even eyes themselves. He thanks these people sincerely but never wears them.He is not tidy, but he knows where everything is: on which chair he left his briefcase, in what area of the kitchen counter he tossed his wallet. He does something with the corners of his mouth when things are not as they should be—when the dog is on the furniture, when the children and their friends make too much noise too late at night, when the red-wine glasses are in the white-wine glass rack. It has now pressed itself permanently into his expression, like the opposite of dimples.“Please. Spare me,” says my friend Nancy, her eyes rolling. “If that’s the worst you can say about him, then you have absolutely no right to complain.” Nancy says her husband, Bill, a tall gangly scarecrow of a guy, leaves a trail of clothing as he undresses, like fairy-tale breadcrumbs. He once asked her where the washing machine was. “I thought it was a miracle that he wanted to know,” she says when she tells this story, and she does, often. “It turned out the repairman was at the door and Bill didn’t know where to tell him to go.”Our washer is in the mudroom, off the kitchen. There is a chute from above that is designed to bring the dirty things downstairs. Over the years, our children have used the chute for backpacks, soccer balls, drumsticks. Slam. Slam. Slam. “It is a laundry chute,” I cry. “Laundry. Laundry.”Laundry is my life, and meals, and school meetings and games and recitals. I choose a cardigan sweater and put it on the chest at the foot of the bed. It is late April, nominally spring, but the weather is as wild as an adolescent mood, sun into clouds into showers into storms into sun again.“You smell,” I hear Alex say to Max from the hallway. Max refuses to reply. “You smell like shit,” Alex says. “Language!” I cry.“I didn’t say a word,” Ruby shouts from behind the door of her room. Hangers slide along the rack in her closet, with a sound like one of those tribal musical instruments. Three thumps—shoes, I imagine. Her room always looks as though it has been ransacked. Her father averts his head from the closed door, as though he is imagining what lies within. Her brothers are strictly forbidden to go in there, and, honestly, are not interested. Piles of books, random sweaters, an upended shoulder bag, even the lace panties, given that they belong to their sister—who cares? I am tolerated because I deliver stacks of clean clothes. “Put those away in your drawers,” I always say, and she never does. It would be so much easier for me to do it myself, but this standoff has become a part of our relationship, my attempt to teach Ruby responsibility, her attempt to exhibit independence. And so much of our lives together consists of rubbing along, saying things we know will be ignored yet continuing to say them, like background music.Somehow Ruby emerges every morning from the disorder of her room looking beautiful and distinctive: a pair of old Capri pants, a ruffled blouse I bought in college, a long cashmere cardigan with a moth hole in the sleeve, a ribbon tied around her hair. Ruby never looks like anyone else. I admire this and am a little intimidated by it, as though I had discovered we had incompatible blood types.Alex wears a T-shirt and jeans. Max wears a T-shirt and jeans. Max stops to rub the dog’s belly when he gets to the kitchen. She narrows her eyes in ecstasy. Her name is Virginia, and she is nine years old. She came as a puppy when the twins were five and Ruby was eight. “Ginger” says the name on the terra-cotta bowl we bought on her first Christmas. Max scratches the base of Ginger’s tail. “Now you’ll smell like dog,” says Alex. The toaster pops with a sound like a toy gun. The refrigerator door closes. I need more toothpaste. Ruby has taken my toothpaste. “I’m going,” she yells from the back door. She has not eaten breakfast. She and her friends Rachel and Sarah will stop at the doughnut shop and get iced coffee and jelly doughnuts. Sarah swims competitively and can eat anything. “The metabolism of a hummingbird,” says my friend Nancy, who is Sarah’s mother, which is convenient for us both. Nancy is a biologist, a professor at the university, so I suppose she should know about metabolism. Rachel is a year older than the other two, and drives them to school. The three of them swear that Rachel drives safely and slowly. I know this isn’t true. I picture Rachel, moaning again about some boy she really, really likes but who is insensible to her attentions, steering with one hand, a doughnut in the other, taking a curve with a shrieking sound. Caution and nutrition are for adults. They are young, immortal.“The bus!” Alex yells, and finally Max speaks. This is one of the headlines of our family life: Max speaks. “I’m coming,” he mumbles. “Take a sweatshirt,” I call. Either they don’t hear or they don’t care. I can see them with their backpacks getting on the middle-school bus. Alex always goes first.“Do we have any jelly?” Glen asks. He knows where his own things are, but he has amnesia when it comes to community property. “It’s where it’s always been,” I say. “Open your eyes and look.” Then I take two jars of jelly off the shelf inside the refrigerator door and thump them on the table in front of him. I can manage only one morning manner, so I treat my husband like one of the children. He doesn’t seem to mind or even notice. He likes this moment, when the children have been there but are suddenly gone. The dog comes back into the room, her claws clicking on the tiled floor. “Don’t feed her,” I say, as I do every morning. In a few minutes, I hear the messy chewing sounds as Ginger eats a crust of English muffin. She makes a circuit of the house, then falls heavily at my feet.After he has read the paper, Glen leaves for the office. He has early appointments one day a week and late ones three evenings, for schoolchildren and people with inflexible jobs. His office is in a small house a block from the hospital. He pulls his car out of the driveway and turns right onto our street every single morning. One day he turned left, and I almost ran out to call to him. I did open the front door, and discovered that a neighbor was retarring the driveway and a steamroller was blocking the road to the right. The neighbor waved. “Sorry for the inconvenience,” he called. I waved back. Read more

Features & Highlights

- Mary Beth Latham has built her life around her family, around caring for her three teenage children and preserving the rituals of their daily life. When one of her sons becomes depressed, Mary Beth focuses on him, only to be blindsided by a shocking act of violence. What happens afterward is a testament to the power of a woman’s love and determination, and to the invisible lines of hope and healing that connect one human being to another. Ultimately, as rendered in Anna Quindlen’s mesmerizing prose,

- Every Last One

- is a novel about facing every last one of the things we fear the most, about finding ways to navigate a road we never intended to travel.