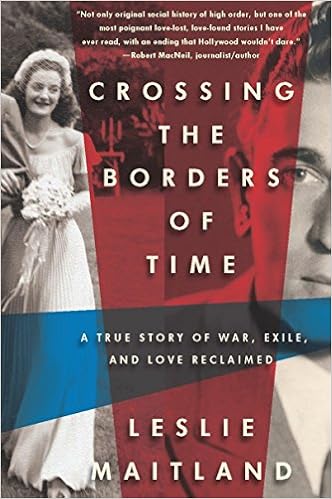

Crossing the Borders of Time: A True Story of War, Exile, and Love Reclaimed

Paperback – Bargain Price, April 17, 2012

Description

Essay by Leslie Maitland “During the fall that my father was dying, I went back to Europe and found myself seeking my mother’s lost love. I say I went back almost as if the world my mother had fled and the dream she abandoned had also been mine, because I had grown to share the myth of her life.” With these opening words, I invite readers on a tumultuous journey to times and places whose misty imaginings had been with me always. Gripped by my mother’s accounts of love, persecution, war, and escape, I embraced the mission to pass them on to a new generation. But as a journalist, I felt compelled to ground memory in history. I needed to be able to state with assurance, for myself as well as my readers: this is what happened. And so I set out to explore the terrain of the past and recreate a world that was gone. Confronting Hitler’s dread transformation of Europe is no simple matter, and nowhere more complex, perhaps, than in France. Pursuit of the facts sent me on five trips there, as well as to Germany, Canada, and Cuba. Over the years I spent delving through archives and into a period that must not be forgotten, my scope enlarged to include those whose lives intersected my mother’s, many of whom did not survive to tell their own stories. As a result, I came to believe that the context in which my mother, Janine, and her true love, Roland, had found, adored, and lost one another was essential to understanding their passion. Beyond that, compared to the hellish suffering inflicted on millions under the Nazis, the thwarted love of two young people was something I wanted to keep in perspective. As Rick insisted to Ilsa in the 1942 film Casablanca , speaking of their own anguished love triangle: “It doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” Losing Roland felt like a death to Janine in 1942, but her escape on a ship sailing from France at the eleventh hour placed her among the most fortunate few in that era of terror. And so my aim was to weave the golden thread of their romance through a broad and vivid historical canvas. Crossing the Borders of Time brought me face to face with “characters” I had long known through my mother’s stories. Several, confused by my physical likeness to a younger Janine they still remembered, unwittingly helped to foster an uneasy sense that I had slipped through time and was somehow reliving my mother’s experience. Others have contacted me since the book’s publication to add their own postscripts. With news articles about the book appearing in Germany, I have received surprising messages filled with reminiscences, regrets, and kind wishes. A man of 80, for instance, recalled the alarming first sight of his own father weeping in 1938 – his grief prompted by learning that his generous Jewish employer, my grandfather Sigmar, was fleeing the country. “Maybe it is good for you to know that during the horrible years of the persecution of Jews,” he wrote, “some people felt and suffered with you.” From outside Berlin, a woman emailed to say that the Wehrmacht soldier described in my book as having proposed marriage to Janine in 1940 in order to save her from Hitler had actually been a member of her family! “Just think,” she mused, “had circumstances been different and had your mother fallen for him, we could be related today.” Still more wrote simply to thank me and to recount their own stories of heartbreaking loss and of seeking new lives and fresh purpose in strange places. It is an irony of time and technological progress that unknown readers have been able to reach me and share such personal contacts. Janine and Roland – separated through no fault of their own – were obliged to make hard compromises. My own life is a consequence of their painful rupture. I am grateful that in pursuing their story I could help to shape the way that it ended. A Look Inside Crossing the Borders of Time On the right, Janine Maitland with daughter Leslie; on the left, Janine’s sister Trudi with daughter Lynne Click here for a larger image Alice Heinsheimer, Janine’s mother, before her marriage in Germany in 1920 Click here for a larger image Roland Arcieri, Janine’s love, in Lyon, France, 1942 Click here for a larger image Janine’s official identity card from Gray, France, 1939 Click here for a larger image “One of those sweeping, epic, romantic novels that seems tailor-made for the Oscars and a long summer afternoon. xa0Except it’s real! xa0Leslie Maitland has the rare ability to bring history, adventure, and love alive.” —Bruce Feiler, New York Times best-selling author of Walking the Bible and Abraham “How the small flame of an undying love can illuminate the darkness of a tragic era. This elegantly told story is for everyone." —James Carroll, New York Times best-selling author of Jerusalem, Jerusalem and Constantine’s Sword “A mesmerizing memoir of one family's shattering experience during World War II. xa0It's a tale at once heartbreaking and uplifting.” —Linda Fairstein, New York Times best-selling author of Silent Mercy “Not only original social history of a high order, but one of the most poignant love-lost, love-found stories I have ever read, with an ending that Hollywood wouldn't dare.” —Robert MacNeil, Journalist-author“Maitland is a brilliant reporter who knows what questions to ask and how to get her story. xa0Written with the precision of a historian, the result is a work I could not put down and scarcely wanted to end.” —Michael Berenbaum, former director of the Holocaust Research Institute at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum“A love affair thwarted by war, distance and a disapproving family became the defining story of Leslie Maitland’s mother's life, and by extension, her own. xa0What happens next is surprising indeed.” —Cokie Roberts, NPR and ABC News analyst and author . “A poignantly rendered, impeccably researched tale of a rupture healed by time.” — Kirkus Reviews “This is a worthy testament to how war and displacement conspire against personal happiness.” — Publisher’s Weekly “Maitland’s personal account ofxa0 her family is a major contribution to history interlaced with a lovely love story.” –Arts and Leisure News “This is a fascinating story of thwarted love, longing, and the travails of one woman and one family within the broader context of war and persecution. Maitland includes a treasury of old family photographs and documents to enhance this incredible story of the gauzy intersection of memory and fact.” –Vanessa Bush, Booklist (starred review)“[Maitland] writes with a clear, candid journalist’s eye and manages to remove herself from the story, yet place herself into the narrative at the same time. [She] writes...with insight and honesty. She closes this noteworthy read with poetic understanding and gentleness.” – Jewish Book Council “ Schindler’s List meets Casablanca in this tale of a daughter’s epic search for her mother’s prewar beau-50 years later.” – Good Housekeeping “[A] gripping account of undying love-a tale of memory that reporting made real.” – Town & Country “ Crossing the Borders of Time is more beautiful than a novel because of the power of its true story and the richness with which it is told.” –Neal Gendler, The American Jewish World “A gripping true-life tale of victims of Nazi persecution and one survivor's quest for her lost love.” – Shelf Awareness “Sometimes the truth is not “stranger than fiction” but more compelling than fiction, and that’s the case here.xa0 Any reader who likes exciting World War II drama and a good love story will be drawn to this book. Well written and captivating, its story will stay with readers well after the book is finished.” – Library Journal “An absorbing true account of romance, resilience, and survival during the years leading up to and during World War II, set against the backdrop of the Holocaust and the harrowing social history of mid-20th-century France.” – The Daily Beast “ Crossing the Borders of Time will bewitch you. There is no fictionalized account of long-lost love that could be as compelling as this valentine to Leslie Maitland’s parents and the sad situations that threatened to ruin their moral compasses throughout their entire lives. Simply put, this is an unforgettable tale.” –Book Reporter " Crossing the Borders of Time is a hair-raising tale of escape and survival, where crossing a border means everything. But sometimes, in this complicated world of loss, change and missed opportunities, it is just as amazing that love can make it across the biggest border of all: the border of time. Highly recommended." -American Girls Art Club in Paris "The author makes fine use of her journalistic skills to conduct the search and to write about it, producing a narrative that is both informative and electrifying. History and the family saga combine in an informative and heart-warming tale that grips the reader's attention." -Indianapolis Jewish Post & Opinion "This book gives a valuable window into how real people coped with war and also tells a compelling love story with modern twists. I highly recommend it." -Book Buzz Leslie Maitland is an award-winning former New York Times investigative reporter and national correspondent who covered the Justice Department. She appears regularly on the Diane Rehm Show on NPR to discuss literature. She lives with her husband in Bethesda, Maryland. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. I came into the book of life almost two years after my parents marxadried, disadvantaged, as are we all, by not knowing what occurred bexadfore. Who can grasp that as a child? Unsuspecting, we fall into the plot of time and try to piece the past together. We puzzle over mysterious scars, we catch the scent of doubt in the air, and we stumble over relics of dreams that litter the intimate family landscape. Years go by before we discern our place in the story, yet as we open our eyes on the dawn of our lives, we may imagine the world begins with us. The day that I entered the tale I am telling was one of the very few times in life I managed to show up anywhere early. Shortchanged at only eight months, I was ejected into the world prematurely, which apparently left me feeling aggrieved. I would later have to hear many times how I flailed and kicked so furiously in my bassinet that the nurses resorted to binding my legs together in the attempt to stop me from bruising myself. Then and there, they warned my mother that it appeared she would have a somewhat difficult case on her hands. Did that sour professional view worsen the mood she was in the following day when my father failed to arrive until afternoon to visit us both at the hospital? He bounded into her private room sporting a novelty tie with a proud announcement splashed in yellow on a burxadgundy background: “It’s a Girl! It’s a Girl! It’s a Girl!” the tie squawked the news in a pattern of print from collar to belt. But that was not all. He arrived with a dozen fragrant gardenia corsages, which he proxadceeded to pin on all the nurses on the obstetrics ward. By the time he returned to my mother’s bedside, the florist’s box with its waxed layers of green tissue paper was empty: in a flush of munificence, Len had given all the creamy flowers away, neglecting to save a corsage for his wife. Thus it began. The first battle I witnessed between my parents evolved from my father’s needy compulsion to enchant other women. “By all means, take those too.” Janine pointed to a lavish display of long-stemmed red roses, a gift from Norbert, still based in Germany. “I’m sure there must be some nurses you missed. You could always try a different floor.” Later that night after Len went home—and before a nurse extolling his charms wheeled me off to sleep with my newborn peers—my mother and I indulged in a solid postpartum cry together. They were not the last tears my father would cost us. A basic premise of my parents’ marriage was my mother’s refusal to leave her parents. Having failed to leave them for Roland, nothing could make her move away once she’d married someone else. When Herbert offered Len a job, Janine insisted he turn it down because, while it was a leg up to a great career, it involved a six-month posting to Japan. No, she said, not possible even temporarily for her to leave New York. Reluctantly rejecting Herbert’s offer, Len continued in the engineering salesman’s job that cast him as a wandering peddler. And again, six years later, when Janine went with him on a business trip to California, in deference to her feelings Len sacrificed a lucrative opxadportunity that would have meant their moving to Los Angeles. “ The people here keep telling me what a remarkable husband I have, and they offered him a very important job in the factory, which he would love to accept ,” Janine wrote home to Trudi. But the company president told her that Len had turned it down out of his “respect” for her attachment to her family — “ born out of the troubles we went through together .” She confided to Trudi, “ I didn’t realize he was that understanding .” Janine was working now for Mount Sinai Hospital’s chief of carxaddiology, and when it came to household chores, Len initially took upon himself both the laundry and the gritty cleaning. Every Monday evening, he celebrated their Monday wedding with another anniverxadsary present, and at the end of their first year, he gave his bride his handmade voucher—a Gutschein , as her parents termed it—for the belated purchase of a diamond ring. It was an offer she did not accept because she knew that he could not afford it. Happily, he plunged into the family circle and answered now to “Leonardle,” the badisch nickname Alice gave him in token of her growing fondness. So, for the time being, he took it as a fine arrangement when he and Janine found their own apartment literally steps away from his in-laws. Amid a sexadrious postwar housing shortage, they, too, paid the superintendent’s $500 finder’s fee to rent a place across the hall from Janine’s parents. A penthouse on Fifth Avenue would not have pleased her more. From the start, Janine and Trudi with their husbands spent their time together, and they were several sets into canasta on a sticky sumxadmer evening one year after they had married, when Trudi shared alarming news. She had taken Alice to the dentist that afternoon to see about a painful canker sore, and he had raised the possibility their mother’s lesion might be cancerous. “God, no!” Janine burst out. “I’d better get pregnant quickly! If something happens to Mother, I’ll need someone to love!” She tossed out these words unthinkingly, like easy discards from a well-planned hand, and Len pretended not to hear her. Afterward, the devastating impact of her statement hit her, and she felt guilty, even as her goal remained. By summer’s end, while fears for Alice proved ungrounded, Janine and Trudi both were pregnant, and ever locked in rivalry, they conceived just weeks apart, so that Trudi’s daughter Lynne would be born merely twenty days ahead of me. “What goes through a man’s mind, driving seven hundred miles home without having earned a cent?” Arthur Miller wrote of the salesman’s plight in the year that I was born. In my father’s case, his letters from the road in March 19uf7349 voice the ache of exile from his cozy home and distance from his pregnant wife. “ Ich bin ganz allein in der großen Welt ,” I am all alone in the big world, he wrote to Janine from Hudson, New York, repeating words he knew that she had used in childhood, writing home in misery from her prescribed confinexadment in the Alps. “ I’m very lonesome without you and can’t wait till I get home to you again ,” he bewailed from Syracuse . “ It’s awful not to be near enough to call you during the day, and the nights are intolerable .” xa0Finding my father’s needy, youthful letters only after he had died was a wrenching revelation to me. Even now, I read them with overxadwhelming grief of loss. How I wish I might have known this tender, ardent, open man. Syracuse—My dearest, I think of you constantly and pray that you are all right—I miss you so terribly that it makes me sick somexadtimes. . . . It makes me so nervous and uneasy to be away that all I can think of is getting thru and getting home. . . . My darling, I love you so much and I want you with me always . . . I’ve been a good boy and haven’t even done anything bad—you’d be proud of me. But I have no desire for any one but you. . . . Take me in your arms tonight. I need you, and I’m loving you with all my heart. Len He called her almost every day and shared his schemes to organize his business stops, scattered in far-flung towns around the state, in order to steer home to her as soon as possible. “ More and more ,” he wrote from Utica, describing his new outlook, “ I realize that family life is really the most important thing and can’t wait to get home to start it again with the girl of my dreams .” Longing for her robbed him of necessary patience to study for his state engineering license test, he fretted, even as he also worried over racking up sufficient sales to justify his trip expenses to his boss. “ I’m shaking oak trees ” in hopes of knocking loose potential business, he wrote, but the market was so bad that “ each sale, no matter how small, is like pulling teeth—impacted molars .” But the letter that most captured me was one that showed how poorly Leonard understood the rival he was battling. What was Janine thinking when she shifted to her husband the anthem of her first roxadmance? “J’Attendrai” was the secondhand love song that Len sang aloud in his hotel room to fill the cold space of his solitude. He could not have known the song belonged irrevocably to another man or that its words of loss and longing would conjure up Roland for her. I miss you muchissimo and wonder how the devil I sleep at all without you. I’ve been so allein that I keep talking to myself nights to keep up a conversation and then sing “J’Attendrai” to you for an encore. A few more days of this and I’ll be as nutty as a fruitcake so please don’t mind if I seem a little peculiar at first when I return. I’m a-lovin and a-worshippin that girl of mine—you know who she is—yes, Hannele, and please tell her if you can. All my love and a thousand hugs and kisses, Len When I read the letters of that eager, boyish husband, I see him on a marital minefield, like the “wide open flats” of the windy corporate campuses he described, but this one rigged with potent memories of an unseen rival. Len, Janine, and Roland—each betrayed by love and war. In the fall of 1948, Sigmar and Alice left the city for a few weeks’ visit with Heinrich’s family in Buffalo. This annual pilgrimage and a two-week summer stay at a lake in the Catskills—he reading, she knitting— were the couple’s only forays from the confines of their small apartment where their daily lives were governed by routine and economy. Already sixty-two when he reached the States, Sigmar had not attempted to get a job. Instead he worked at learning stratagems of stock investing—this notwithstanding the fact that his prospects for growing capital were significantly diminished when the great inheritance he had anticipated in America proved much smaller than expected. His original large bequest from one wealthy older brother had dwindled throughout the many years he couldn’t claim it or direct the way it was invested. And the widow of another older brother who had died childless many years before, leaving a vast estate and similarly generous bequests to his sibxadlings, had managed to circumvent the will to her advantage. Yet when Sigmar’s surviving brothers and sisters sued to win their lawful shares, he refused to go along with them. xa0“ I should sue my brother’s widow?” Sigmar demanded with increxaddulity, denouncing his siblings’ lawsuit as an ugly tactic, regardless of her assets or greedy machinations. What money Sigmar gained from the first inheritance went to repayxading with interest all his debts to Herbert, Maurice, and Edy, and the balxadance he endeavored to invest. Every day he went to Wall Street to learn beside his cousin Max, who was trying to become a broker. In the risky ventures of the market, though, Sigmar’s belated apprenticeship proved more costly than profitable. He watched, now in helpless indecision, then in loyalty to those few stocks he termed his “darlings,” as the value of his holdings fell. In that context, calling home one day from Buffalo, he told Janine to search his files to verify the purchase price of shares that now seemed poised to plummet even lower. The blinds were drawn and everything in tidy order in her parents’ second-floor apartment when Janine, then ten weeks pregnant, sat down at Sigmar’s mahogany keyhole desk in the living room. Above her head, a large framed picture of President Franklin D. Roosevelt reflected her father’s gratitude to his new country. After years of livxading with the visages of Hitler and Pétain leering at him everywhere, Sigmar had uncharacteristically sent away for this poster-sized arxadtistic tribute to FDR, believing, with many Jewish refugees, that the patrician wartime president had done his best to rescue them. (That Roosevelt had failed to open the gates of immigration to Europe’s victims anywhere near as widely as he could have, or that his adminisxadtration had refused to accede to Jewish pleas to bomb the railway lines leading to Nazi death camps, were facts not yet known.) In years to come, Janine would not remember whether the finanxadcial statement Sigmar needed had been difficult to find, obliging her to expand her search of his private files, or—she acknowledged the possibility—it was random, audacious snooping that broadened her explorations. Either way, like Pandora, she would regret her curiosxadity, when drifting from the broker’s statements, her eyes picked out a telegram from the International Committee of the Red Cross. It announced that a Roland Arcieri had enlisted help in France through the Red Cross Tracing Service to determine the whereabouts of a Janine Günzburger in New York. In the event this message reached her, the Red Cross instructed her to get in touch—promptly, please. In an instant of total joy she forgot the sorry waste of tortured years, forgot her husband, forgot the child nestling deep inside her, and she responded to the wondrous fulfillment of her greatest wish: finally, finally, Roland was calling out for her! At last, after all her years of patient waiting, here was clear-cut proof of Roland’s enduring love. Yes, with the urgency of a telegram, her lover was crying out to her. In a fever of excitement, she studied the telegram for directions on responding. But when had it arrived? She read it again, flipped it over, hunted vainly for its envelope, but no date could be found. Why had no one shared this with her? A cloud of dark suspicion slowly slid across her heart. Months or even years could well have passed since this telegram arrived. She struggled with the realization that its burial among Sigmar’s papers was proof that he had purposely concealed it. The ground tilted underneath her feet. The father whose steely dicxadtates she had always feared, but whose honor she had never doubted, had acted with unconscionable deception. A wave of nausea seized her. She fought for breath, her legs felt weak, and the room began to turn: Roosevelt, so solemn in his business suit, the violets with their velvet buds uncurling on the windowsill, Lindt chocolates in a porcelain dish that Alice offered every guest, the Aufbau ’s latest issue folded on the coffee table, a cut-glass ashtray next to Sigmar’s reading chair—all these ordinary objects now seemed sly and slippery. Like painted scenery on a stage, her parents’ gemütlich living room disguised a disappointing world of secrets and duplicity. She gripped the corner of the desk. An unaccustomed sense of rage and violation overcame her, and she did not know what to do with it. Her thoughts went racing backward in useless search of explanations to make forgiveness possible. Did this mean there had been letters too? Obviously so! Her love had written, begging her to come to him, and not receiving any anxadswer, Roland could only have concluded that his letters failed to reach her. Why else would he have turned to the Red Cross Tracing Serxadvice? But hadn’t Norbert given him her address when they got toxadgether in Lyon? Then surely he had written her! How terrible for him, through years of doubt and silence, to be misled into believing that she had forgotten him. With eager fingers and frantic determination to understand the truth of things, she ransacked every drawer of Sigxadmar’s desk, certain that if he saved the telegram, he must have saved the letters too. Surely, the telegram was proof that Father would not have dared destroy them. But there was only that one telegram, saved from the incinerator by its officious pedigree, the sort of communixadcation, she recognized, that no true German like her father, mindful of proper record keeping, would carelessly obliterate. Suspended in time—with a past that now demanded reevaluation, a present that no longer seemed of her own making, and a future robbed of honest choices—Janine spent hours on the floor of her parents’ living room, debating where to go from there. No point in raising the issue with Father. He’d cite his rights—no, his obligation —to protect his lovexadsick daughter from the dangers of pursuing an ill-advised relationxadship. Sigmar would not admit to doing wrong, and it would only drive a wedge between them. And so, respectful of his authority and still devotedly committed to winning his approval, she worked to squelch the anger to which she was entitled. Beyond that, she numbly granted, she could hardly bring the issue to the open without involving Len and showing him how much Roxadland still mattered to her. Why hurt her husband now and taint their marriage, when she couldn’t leave him anyway? For how could she sail back to France anchored by an unborn child? She was fixed to the spot by the growing weight of me within her womb. The golden moment when she might have set a different course was as lost in clouded history as an intercepted telegram hidden in a file drawer. Read more

Features & Highlights

- On a pier in Marseille in 1942, with desperate refugees pressing to board one of the last ships to escape France before the Nazis choked off its ports, an 18-year-old German Jewish girl was pried from the arms of the Catholic Frenchman she loved and promised to marry. As the

- Lipari

- carried Janine and her family to Casablanca on the first leg of a perilous journey to safety in Cuba, she would read through her tears the farewell letter that Roland had slipped in her pocket:

- “Whatever the length of our separation, our love will survive it, because it depends on us alone. I give you my vow that whatever the time we must wait, you will be my wife. Never forget, never doubt.”

- Five years later – her fierce desire to reunite with Roland first obstructed by war and then, in secret, by her father and brother – Janine would build a new life in New York with a dynamic American husband. That his obsession with Ayn Rand tormented their marriage was just one of the reasons she never ceased yearning to reclaim her lost love. Investigative reporter Leslie Maitland grew up enthralled by her mother’s accounts of forbidden romance and harrowing flight from the Nazis. Her book is both a journalist’s vivid depiction of a world at war and a daughter’s pursuit of a haunting question: what had become of the handsome Frenchman whose picture her mother continued to treasure almost fifty years after they parted? It is a tale of memory that reporting made real and a story of undying love that crosses the borders of time.